If you’ve been following along, you’ll have found two common threads running through our Seasons of Play series: (1) play is important for childhood development; and (2) there should be no border between play and learning. The Center for Playful Inquiry’s Susan Harris MacKay and Matt Karlsen go even further in their commitment to play. More than just an educational endeavor, play is a reliable weapon in the fight against fascism.

This belief is rooted in the Italian city of Reggio Emilia and the teaching approach with which it shares a name. Harris MacKay and Karlsen are among the thousands of educators who have come from all over the world to absorb the methods pioneered by Loris Malaguzzi (1920-94). The experience helped the Reggio-inspired Opal School (which served children ages 3-11) and the Portland Children’s Museum to jointly emblematize the play, playful learning and playful research that engage young minds in ways that standard U.S.-based pedagogies generally miss out on. These two institutions both closed in June of 2021, falling victim to pandemic financial woes, but their spirit lives on in the Center for Playful Inquiry.

👉 What Are Reggio Emilia Schools? (The New York Times)

“The mission of the school,” says Harris MacKay, “was not to serve that tiny group of lucky children who won the [charter school] lottery but to become a site of research that was intended to provoke fresh ideas where creativity, imagination and the wonder of learning thrive.”

The Reggio-Emilia approach, Karlsen notes, arose in the years after World War II, when Italian society was asking itself what had happened to make Mussolini’s rise possible and what could be done to keep it from happening again. “It is an anti-fascist pedagogy,” he says, emphasizing that school and society both run on the interaction between people. Is the dynamic top-down, or is the power shared? Do members of the community fear authority, or do they respect each other and gain strength in their solidarity?

Beyond targeting what Harris MacKay calls the false dichotomy between what’s known as free play and what’s known as direct instruction, the Center for Playful Inquiry promotes a wholesale reconsideration of the way teachers are trained. “We talk about adults not walking too far ahead of children, or not following too far behind them, but really just trying to be right alongside them,” she says.

Educators visited Portland from around the country to observe and draw inspiration from the Opal School. “Being based in a school,” Karlsen says, “made things really alive, because children, families and staff were constantly part of this evolving, shifting, surprising, organic experience. We learned a lot from the adults who were visiting, about what kinds of experiences were helpful for them.”

The Opal School’s program of professional development gave rise to the Center for Playful Inquiry (which organizes presentations, and facilitates conversations, planning and reflection) as well as the Studio for Playful Inquiry (an online community for mutual mentorship; also known as the Story Workshop Studio). “As we leave the laboratory of the school behind,” says Harris MacKay, “we meet up with all kinds of people who bring their own background knowledge or expectation of what professional development is.”

Donna King of Children First in Durham, N.C., says, ”So much has been exceptionally enriching about the community and experiences Matt and Susan have created—they are brilliant facilitators, empathic listeners and incisive thinkers—visionaries with a repertoire of skills that make everyone they encounter think more deeply and feel more wholeheartedly.”

Three ways the Center for Playful Inquiry continues to draw upon Reggio:

1. Helping people pay attention to their own context. Harris MacKay and Karlsen were inspired by what they experienced in Italy, but the plan never was to establish a “franchise” of Reggio in Oregon. Their vision was always rooted in their own time and place.

“We were developing some really interesting ideas and some interesting expressions of those ideas,” Karlsen recalls. “When other people came, it wasn’t to say, ‘You should be doing what we’re doing in Portland, at this little spot in Washington Park, and in a children’s museum, in your spot.’ Instead, it was saying, ‘We think this is interesting. What might be the implications to your space?’”

3. Giving educators permission to find their own path. Just as Karlsen and Harris MacKay didn’t set out to copy Reggio, they don’t try to impose a specific method on educators. The experience contrasts starkly with the standard operating procedure for this kind of enterprise, which Karlsen derides as I’m going to show you how to use this binder. And as long as you use this binder, it’s going to work for you and the children that you’re working with.

To capture the dynamic to which they aspire, he makes two comparisons—one, in rock music, to the Velvet Underground (whose debut album came out in 1967); and two, in the culinary arts, to Alice Waters of Chez Panisse (which opened in 1971). In both cases, the influence is vast, but neither icon inspired mere replication. Instead, bands followed the Velvet Underground into sonic and lyrical experimentation, and chefs followed Waters into reimagined ways of preparing and serving fresh ingredients.

3. Drawing strength from reimagining the ways adults interact with each other. Early education isn’t all about children. Equally important is how adults work with their colleagues and with parents. Adults, whether or not they’re officially teachers or not, need to develop their capacity for listening and interpreting what children care most about, and then trying to connect there.

Harris MacKay notes that many of the adults in the profession have not been invited to see themselves as learners, which influences the way that they, then, see children as learners. “Teachers are integral to the experience that children are having,” she asserts. They’re never invisible to the children.”

For Reggio veterans and novices alike, the Center for Playful Inquiry is teaming up with author and literacy expert Kathy Collins for an online course about friendship.

Deep and long-lasting change can take time. Harris Mackay says too many teachers have the mindset that as long as they do what they’ve been trained to do just right, then the children will learn. “That’s just not the way human learning works,” she says. “It’s a slow, gentle process, playing in a lot of different ways, intellectually, with materials and with each other.”

More from the Seasons of Play series:

A Day Trip to Philadelphia Shows What Playful Learning Is—and Isn’t

Part 1 of "Seasons of Play" Series

“Play is an activity enjoyed for its own sake,” writes Diane Ackerman in her 1999 book Deep Play. “It is our brain’s favorite way of learning and maneuvering…. It’s organic to who and what we are, a process as instinctive as breathing.” Researchers continue to explore the many ways that play drives early learning. A recent white paper published by the LEGO Foundation counted 300 studies across over 40 countries that demonstrated a link between play and skill building in […]

Getting Messy in Madison: The 6 Sides of the Upcoming Play Make Learn 2023 Conference

Part 2 of "Seasons of Play" Series

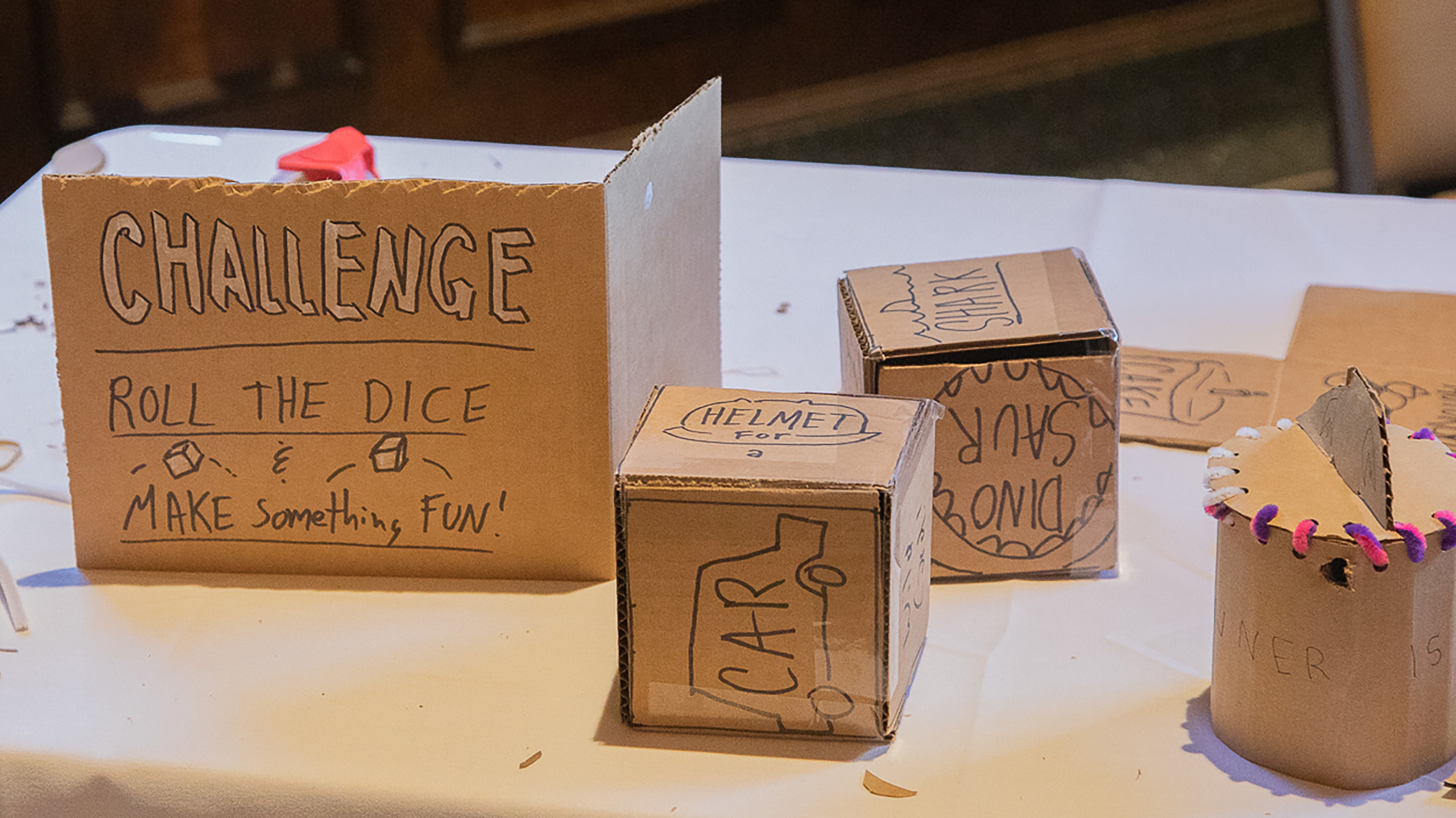

The Play Make Learn conference, taking place July 20-21 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers educators hands-on learning experiences and a chance to connect with colleagues from libraries, museums, schools and the wide world of games. The planners define playful learning quite broadly, says Emily L. Nott, a doctoral student in curriculum and instruction. “We have people who are approaching it from a games perspective, from an arts perspective, from an embodied learning perspective, but one of the common factors […]

The Children’s School in Pittsburgh: Where It’s Hard to Tell Play, Learning and Work Apart

Part 3 of "Seasons of Play" Series

The three-, four- and five-year-olds at the Children’s School at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh had a problem. They had blocks to move on the playground, but they didn’t have the wheelbarrows necessary to get the job done. So they got one of the teachers to help them write a note. Dr. Sharon Carver, who has been running the Children’s School since 1993, did not just chuckle and tape the request to the refrigerator. “We ordered the stuff they asked […]

Can Play ‘Level the Playing Field’ in Chicago? How VOCEL Is Shifting Strategy to Magnify Impact

Part 4 of “Seasons of Play” Series

Jesse Ilhardt is an evangelist for play. Her wildly popular TEDx talk, “How Play Helps a Kid’s Brain Grow,” shot in the friendly confines of Wrigley Field, is full of relatable nuggets like If learning is like a workout for the brain, then play-based learning is the heavy lifting and A couple household materials dropped into the bathtub, and this mundane routine becomes fun and surprisingly energizing bonding time for you and your child. The cofounder and executive director of […]

Tim Gill and Ankita Chachra Discuss How and Why Cities of the Future Can Work Better for Children

Part 5 of “Seasons of Play” Series

Tim Gill’s book Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities is a timely and engaging manifesto, full of maps and charts, pointing to future cities where play happens in streets, squares and green spaces, not just playgrounds. Further, he celebrates public spaces that “nurture contact between families in different social groups.” Ankita Chachra, senior fellow at Capita, recently posted an essay, “Connecting Cities, Young Children and Climate Action,” describing how her dual journeys as an urban planner […]

Inspiring Educators with No Borders Between Play and Learning at the Center for Playful Inquiry

Part 6 in “Seasons of Play” Series

If you’ve been following along, you’ll have found two common threads running through our Seasons of Play series: (1) play is important for childhood development; and (2) there should be no border between play and learning. The Center for Playful Inquiry’s Susan Harris MacKay and Matt Karlsen go even further in their commitment to play. More than just an educational endeavor, play is a reliable weapon in the fight against fascism. This belief is rooted in the Italian city of […]

Building Equity by Building Playgrounds (and More)

Part 7 in “Seasons of Play” Series

Too many communities of color lack access to the spaces and facilities needed for quality play. And even if those spaces do exist nearby, children won’t play there if they don’t feel safe, welcome, included and comfortable. “Playspace Inequity” is the term that the national nonprofit KaBOOM! has given this phenomenon, and the 25 in 5 Initiative is how the organization aims to solve it in five years.

Play Is a Child’s Search for Meaning: Q&A with Brenda Fyfe

Part 8 in “Seasons of Play” Series

To learn more about play’s place in the Reggio Emilia approach, Early Learning Nation magazine spoke to Brenda Fyfe, dean and professor emeritus of the School of Education at Webster University.

My conversation with the Center for Playful Inquiry’s Susan Harris MacKay and Matt Karlsen ignited an intense curiosity about how early learning spaces might become zones for creativity, which sent me to the library (or three) to investigate Reggio Emilia. One text in particular, In the Spirit of the Studio: Learning from the Atelier of Reggio Emilia (2015) powerfully conveyed to me the potential of the atelier (French for studio; this piece will use the words interchangeably). In the book’s […]

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.