The federal Child and Adult Care Food Program works.

One of 15 US Department of Agriculture programs aimed at reducing food insecurity and improving nutrition for America’s vulnerable populations, the CACFP is the primary federal program that helps feed the nation’s youngest children in a variety of child care settings. The program improves child nutrition, supports families, reimburses child care providers and infuses federal dollars into local economies, among other benefits.

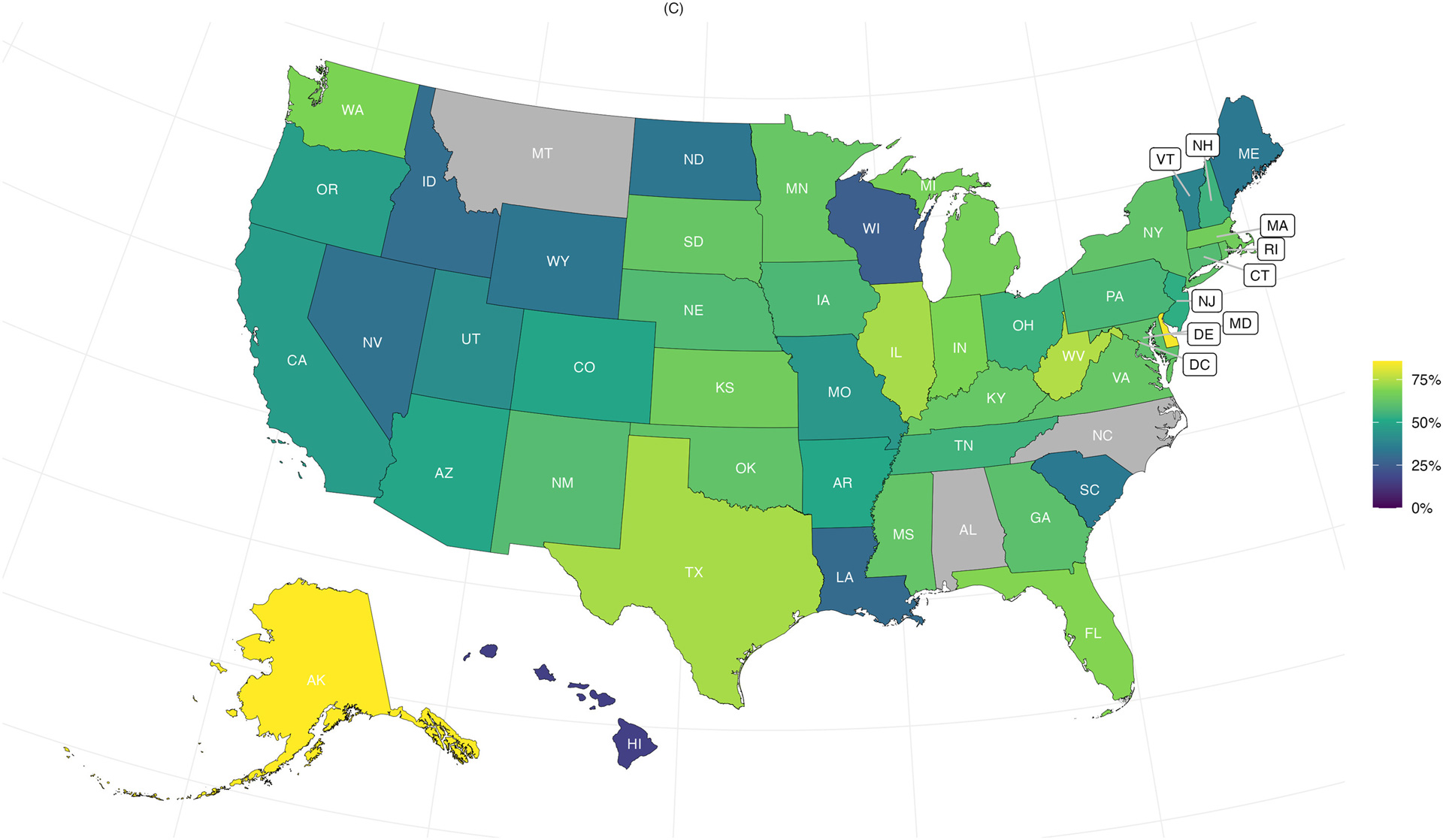

And yet, the first nationwide analysis of data on CACFP just published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine (AJPM) finds the program underused and unevenly accessed throughout the U.S. The study found that of all licensed child care centers in the U.S., just 36.5 percent participated in CACFP. In low-income areas, the number of child care settings using the program varied widely from state to state, ranging from 15.2 percent to 65.3 percent.

For the study, “Federal Nutrition Assistance for Young Children: Underutilized and Unequally Accessed,” researchers analyzed administrative data from the CACFP and child care licensing agencies in 47 states and the District of Columbia for 93,227 licensed child care centers. Alabama, Montana and North Carolina were not included due to incomplete data or non-response. In prior research, they found that many eligible child care providers were not taking advantage of the program; indeed, many had never heard of it.

Lead investigator Dr. Tatiana Andreyeva became aware of providers’ lack of participation as director of Economic Initiatives at the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health. The focus of her research has been the role of economic incentives in food choices, as well as the effects of federal assistance programs on food insecurity, diet quality and access to healthy food in at-risk communities. In earlier research, she had become aware of the CACFP’s surprisingly low provider participation in Connecticut; in surveying providers, she found multiple barriers to participation, including a lack of awareness and piles of paperwork. Supported by a grant from Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Andreyeva and coinvestigators Dr. Timothy E. Moore, Lucas da Cunha Godoy and Erica L. Kenney were able to expand this research nationally.

Statistics Matter

The USDA does not keep statistics on eligible child care settings’ participation in the CACFP. It tracks the number of meals served and daily attendance for the program but doesn’t have a system that tracks participation among eligible programs, though it routinely estimates participation for its larger programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

“As an economist, I can’t understand how this young population is so underfunded, underappreciated,” Andreyeva says. “The CACFP is about nutrition, but if you look at child care and education generally, this age group sees very little public funding. It’s the age where you can get such a positive return on investment, as has been shown in multiple studies. Somehow our society is ready to spend on K-12, but not on children zero to 5. This is the age when you can get a profound return on investment, as has been shown in multiple studies.

“So that’s what motivated me. With this grant, I could study provider child care participation nationwide—and nobody else has done it.”

The researchers collected data from state agencies that oversee licensing and CACFP and merged it with data that helped them identify CACFP-eligible child care centers and learn which of the eligible centers were participating. In other words, a mountain of data.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, most U.S. children regularly are cared for by people other than their parents. Because all CACFP-subsidized meals and snacks must align with the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the children this program serves tend to eat more balanced, nutritious diets than they receive at home. A new study published in the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics concluded that compared with meals provided from home, children in low-income families who receive underwritten meals in child care settings experience greater food security, better health outcomes and are less likely to be admitted to the hospital from the emergency room. In a nation where most young children don’t meet dietary recommendations, child care centers and family daycare homes that participate in this food assistance program can play a unique role in improving the diets of millions of children.

Given those benefits, why wouldn’t these providers rush to sign up for this proven nutrition assistance?

(Credit: American Journal of Preventive Medicine).

Barriers To Participation

Andreyeva’s research highlights a variety of causes, with one key barrier as simple as no one knowing about it. More than half of non-CACFP centers in one state didn’t even know the program existed.

“Do a survey. Ask any parent, even low-income parents, nobody has ever heard about it,” she says. “A lot of child care providers don’t know about it. What we show in our studies is that participation varies by state, but it seems that for the federal government, CACFP is just not a priority.”

Even providers who are aware of the program often are challenged to take all the steps required to be a part of it. Most providers are already struggling to keep their heads above water and one more to-do list for one more program, even one with obvious benefits, can seem impossible.

“They’re already understaffed and overwhelmed, especially after the disaster of the last couple of years. They’re struggling financially and they just don’t have the staff to sort through it.

“I have a PhD and we looked at the application with a nutritionist and we couldn’t figure out how to complete it,” she says. “For child care centers to track income eligibility—it’s a big pain and all the paperwork is just very complicated. No wonder they don’t want to do it.”

One of the complicating factors, she says, is that there have been a few instances of fraud with the CACFP, as recently as during the pandemic, in which millions of dollars were stolen from the government. What had already been a complicated process has become doubly so because of the number of T’s to cross and I’s to dot. The programs are administered through grants-in-aid to the states, which then manage the state program by designated agencies such as their departments of education, health, family and/or social services.

“Participants are usually small businesses, and there are so many of them, oversight can be really challenging for the state. Some states are so concerned with fraud prevention, and seeing that not a penny gets stolen, the feds and states have added so many layers of checks that it can be difficult for a provider to participate. So, a few bad apples have ruined it for others.”

Prior research by this team and others found that other barriers to participation include the complications of serving meals in child care centers, including the availability of food service companies able to provide CACFP-compliant meals at affordable rates; limited equipment and kitchen facilities and staff; local health and state regulations; a lack of parent interest in center-provided meals; and provider concerns about insufficient reimbursement.

“Many participating providers will say that CACFP, through meal reimbursements, pays for food costs, but doesn’t fully cover expenses, especially in more expensive areas with higher food costs,” Andreyeva says.

It Can Be Done

The high levels of CACFP participation in some states after accounting for income differences suggest that some have done an excellent job of getting providers to join the program. Andreyeva has another paper under review in which the researchers interviewed state agencies to see what they were doing—or not doing—to increase participation, so they can share best practices with state agencies, providers and policymakers.

The AJPM analysis has pinpointed multiple potential remedies that could boost participation in the CACFP. Among the researchers’ recommendations, the USDA, state agencies and advocates must:

- Understand why providers decide to participate or not in the CACFP, so solutions can be targeted to these issues.

- Simplify the application process and compliance requirements.

- Provide child care providers with small grants to cover the costs of applying for the program and/or remaining in compliance, such as updating kitchen facilities and equipment or helping them find service vendors.

- Increase the number of sponsoring agencies such as United Way, Catholic Charities and other nonprofits (required for family daycare homes to apply for CACFP), which could ease administrative challenges, particularly for smaller centers.

Policymakers could play a vital role in expanding access to CACFP, including providing adequate funding to administer the program effectively, modernizing data collection to assess and track participation, and conducting extensive outreach to raise awareness of the program.

Andreyeva points to the significant financial implications of failing to utilize this readymade, proven nutrition program. Previous research estimated that underutilization of CACFP in Connecticut left 20,300 children from low-income households without the program’s subsidized meals and cost the state $30.7 million in foregone federal funds. Multiply this figure by the number of qualifying child care centers and daycare homes nationwide that don’t apply, and it adds up to a huge amount of money left on the table.

How much better it would be for our nation’s youngest children if nutritious food were on the table instead.

Resources

The article, Federal Nutrition Assistance for Young Children: Underutilized and Unequally Accessed, is available online in advance of its publication in the January 2024 issue of the American Journal of Preventative Medicine, published by Elsevier.

Child Care Feeding Programs Associated with Food Security and Health for Young Children from Families with Low Incomes This study recently published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics suggests that child care-provided meals likely supported by the CACFP are related to better health and food security for low-income families with young children.

The University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health promotes solutions to food insecurity, poor diet quality and weight bias through research and policy.

Fact Check:

USDA has 15 nutrition assistance programs: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=104145

Differences in preschool-age children’s dietary intake between meals consumed at childcare and at home. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28239540/

National Center for Education Statistics Statistics on Children in Child Care “In 2019, approximately 59 percent of children age 5 and younger and not enrolled in kindergarten were in at least one weekly nonparental care arrangement, as reported by their parents. Among children in a weekly nonparental care arrangement, 62 percent were attending a day care center, preschool, or prekindergarten (center-based care), 38 percent were cared for by a relative (relative care), and 20 percent were cared for in a private home by someone not related to them (nonrelative care).”

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.