Play is an activity enjoyed for its own sake,” writes Diane Ackerman in her 1999 book Deep Play. “It is our brain’s favorite way of learning and maneuvering…. It’s organic to who and what we are, a process as instinctive as breathing.” Researchers continue to explore the many ways that play drives early learning. A recent white paper published by the LEGO Foundation counted 300 studies across over 40 countries that demonstrated a link between play and skill building in young children.

Early Learning Nation magazine’s new series “Seasons of Play,” highlight recent developments in playful learning and capture the thinking of the field’s leading figures. Read them all. Enjoy!

“Don’t underestimate the value of play,” warns Hartwick College’s Laurel Bongiorno in a recent blog for the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). Cognitive, social and literacy skills, along with vocabulary and physical abilities all get a workout when the little ones play. And while nobody invented playful learning, one of the world’s most influential champions was Loris Malaguzzi (1920-94), founder of child care centers and preschools in Reggio Emilia, Italy. (Learn more with this terrific New York Times primer on this educational philosophy.)

To learn more about play’s place in the Reggio Emilia approach, Early Learning Nation magazine spoke to Brenda Fyfe, dean and professor emeritus of the School of Education at Webster University. She serves on the board of the North American Reggio Emilia Alliance and coedited Affirming the Rights of Emergent Bilingual and Multilingual Children and Families (2023).

Mark Swartz: When did you first encounter Reggio Emilia?

Brenda Fyfe: In 1990, I was teaching at Webster University’s campus in Iceland near the NATO base. Many Nordic countries had connected with Reggio Emilia long before anybody in the U.S. did. So I visited Italy, and I was awestruck. A Reggio classroom is a lovely place to be. You want to join the play; you want to play with everything. And yet there’s a sense of calm and peace. In part because it’s very soft and it doesn’t jump out and bombard you like some classrooms do with the primary colors and the letters all over the wall and that sort of thing. It’s soft and it’s peaceful, and yet it’s rich and stimulating, because there are materials there and there’s color, but it’s done in a way that helps you to calm down and not want to jump out of your chair. I returned every year until Covid.

Swartz: You belonged to a generation of educators who helped to popularize Reggio in the United States.

Fyfe: Back then, all the literature that I could find was either in Icelandic or Italian. Lella Gandini was the key liaison between the U.S. and Reggio Emilia. She had been a doctoral student in Italy, and she brought knowledge of the Reggio Emilia approach and helped to organize an exhibit called The Hundred Languages of Children, which highlighted the brilliance of children that they uncover and make visible through that exhibit. (The Hundred Languages of Children is also the title of an influential book.) Leila and I built partnerships and we created programs together. In St. Louis, I organized a group of educators from about five different schools, originally, to come together as a study group.

👉Discover Leila Gandini’s Reggio reading recommendations

Swartz: Let’s talk about Reggio and play.

Fyfe: Carla Rinaldi calls play a child’s search for meaning. Play is the way that children deal with their reality and make sense of their world. And it gives them a sense of freedom, too, and agency. Children express themselves through materials, through music, movement, construction, sculpture, drawing, painting, all of what they call expressive languages.

Swartz: So it isn’t just for fun.

Fyfe: And it’s never completely free play, either. The environment is set up; the materials are chosen. It’s not just let the kids go do whatever they want, you observe and document and then study it. Reggio founder Loris Malaguzzi described the environment as the “third teacher” (alongside the two co-teachers in the classroom).

It’s the idea of using materials to communicate ideas, feelings, thoughts and experiences. And it’s done in a playful way. Children are exploring and experimenting and they’re talking while they’re painting and they’re interacting with friends, and they’re looking at each other’s work and commenting on it.

Swartz: How can an educator tell the play is going the way it’s supposed to?

Fyfe: When it’s really good play, you’re negotiating your experience. If it’s a dramatic play, for example, children are talking; they’re designing ideas; they’re talking about it with each other. We talk about this idea of design, documentation and discourse as part of the negotiated learning process. Group play is a negotiation.

👉Read “Negotiated Learning through Design, Documentation, and Discourse,” George Forman and Brenda Fyfe’s chapter in The Hundred Languages of Children

Swartz: These are life skills. Design, documentation and discourse are things you’re going to use in the workplace and with your family and then life later on.

Fyfe: And even with the materials, you’re kind of negotiating your own understanding of it and your use of it by manipulating it.

Swartz: How does this concept apply to the youngest children?

Fyfe: Even if infants and toddlers don’t have words, they’re watching. What are they looking at? How are they approaching it or how are they touching it?

Swartz: What are some of American Reggio’s innovations in recent years?

Fyfe: The first one that comes to mind is called Border Crossings, from 2019, where they’ve looked at children exploring the outdoors. They’ve helped children to augment their playful observations with technology. They put digital cameras into the hands of children to take a photograph of what they see, and they come back to the images later and reflect on it. So play can be very sophisticated. Play with young children can involve materials, each other, but also technology.

Swartz: It’s a very demanding process for educators.

Fyfe: Yes, and it’s also very energizing in the way it makes you slow down and listen to children. When most of us think about teaching, we picture a lesson plan and a sequence of experiences, and then closure. But rather than letting the plan drive you, you let it open you up to seeing what you didn’t anticipate.

Swartz: Could you say more about the teacher’s role?

Fyfe: The teacher gets involved without being intrusive, without being directive, but you get into the groove of the way the children are thinking. You want children to be in that space of being free to think and act in the moment. I always think of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, co-founder of the field of positive psychology, who originated the concept of “flow.” That’s the perfect image for me of what play is. We like to say the teacher’s role is to toss the ball in a way that the child wants to toss it back to you.

More from the Seasons of Play series:

A Day Trip to Philadelphia Shows What Playful Learning Is—and Isn’t

Part 1 of "Seasons of Play" Series

“Play is an activity enjoyed for its own sake,” writes Diane Ackerman in her 1999 book Deep Play. “It is our brain’s favorite way of learning and maneuvering…. It’s organic to who and what we are, a process as instinctive as breathing.” Researchers continue to explore the many ways that play drives early learning. A recent white paper published by the LEGO Foundation counted 300 studies across over 40 countries that demonstrated a link between play and skill building in […]

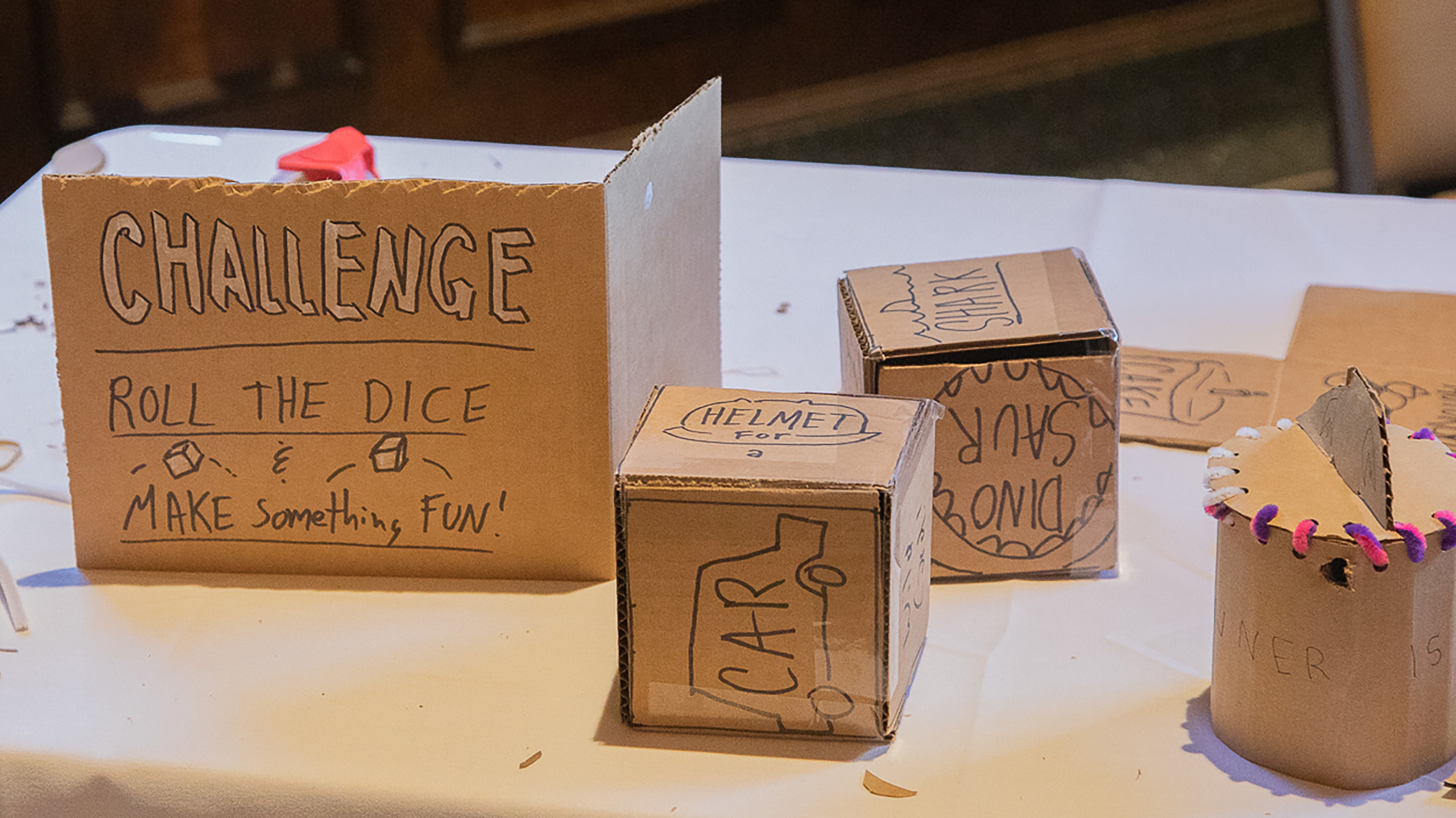

Getting Messy in Madison: The 6 Sides of the Upcoming Play Make Learn 2023 Conference

Part 2 of "Seasons of Play" Series

The Play Make Learn conference, taking place July 20-21 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers educators hands-on learning experiences and a chance to connect with colleagues from libraries, museums, schools and the wide world of games. The planners define playful learning quite broadly, says Emily L. Nott, a doctoral student in curriculum and instruction. “We have people who are approaching it from a games perspective, from an arts perspective, from an embodied learning perspective, but one of the common factors […]

The Children’s School in Pittsburgh: Where It’s Hard to Tell Play, Learning and Work Apart

Part 3 of "Seasons of Play" Series

The three-, four- and five-year-olds at the Children’s School at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh had a problem. They had blocks to move on the playground, but they didn’t have the wheelbarrows necessary to get the job done. So they got one of the teachers to help them write a note. Dr. Sharon Carver, who has been running the Children’s School since 1993, did not just chuckle and tape the request to the refrigerator. “We ordered the stuff they asked […]

Can Play ‘Level the Playing Field’ in Chicago? How VOCEL Is Shifting Strategy to Magnify Impact

Part 4 of “Seasons of Play” Series

Jesse Ilhardt is an evangelist for play. Her wildly popular TEDx talk, “How Play Helps a Kid’s Brain Grow,” shot in the friendly confines of Wrigley Field, is full of relatable nuggets like If learning is like a workout for the brain, then play-based learning is the heavy lifting and A couple household materials dropped into the bathtub, and this mundane routine becomes fun and surprisingly energizing bonding time for you and your child. The cofounder and executive director of […]

Tim Gill and Ankita Chachra Discuss How and Why Cities of the Future Can Work Better for Children

Part 5 of “Seasons of Play” Series

Tim Gill’s book Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities is a timely and engaging manifesto, full of maps and charts, pointing to future cities where play happens in streets, squares and green spaces, not just playgrounds. Further, he celebrates public spaces that “nurture contact between families in different social groups.” Ankita Chachra, senior fellow at Capita, recently posted an essay, “Connecting Cities, Young Children and Climate Action,” describing how her dual journeys as an urban planner […]

Inspiring Educators with No Borders Between Play and Learning at the Center for Playful Inquiry

Part 6 in “Seasons of Play” Series

If you’ve been following along, you’ll have found two common threads running through our Seasons of Play series: (1) play is important for childhood development; and (2) there should be no border between play and learning. The Center for Playful Inquiry’s Susan Harris MacKay and Matt Karlsen go even further in their commitment to play. More than just an educational endeavor, play is a reliable weapon in the fight against fascism. This belief is rooted in the Italian city of […]

Building Equity by Building Playgrounds (and More)

Part 7 in “Seasons of Play” Series

Too many communities of color lack access to the spaces and facilities needed for quality play. And even if those spaces do exist nearby, children won’t play there if they don’t feel safe, welcome, included and comfortable. “Playspace Inequity” is the term that the national nonprofit KaBOOM! has given this phenomenon, and the 25 in 5 Initiative is how the organization aims to solve it in five years.

Play Is a Child’s Search for Meaning: Q&A with Brenda Fyfe

Part 8 in “Seasons of Play” Series

To learn more about play’s place in the Reggio Emilia approach, Early Learning Nation magazine spoke to Brenda Fyfe, dean and professor emeritus of the School of Education at Webster University.

My conversation with the Center for Playful Inquiry’s Susan Harris MacKay and Matt Karlsen ignited an intense curiosity about how early learning spaces might become zones for creativity, which sent me to the library (or three) to investigate Reggio Emilia. One text in particular, In the Spirit of the Studio: Learning from the Atelier of Reggio Emilia (2015) powerfully conveyed to me the potential of the atelier (French for studio; this piece will use the words interchangeably). In the book’s […]

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.