On a recent sunny Friday morning at the Daposka Ahnkodapi School in Pawhuska, Okla., the day began with weekly circle time for students, led by their teacher, Cameron Pratt. At many elementary schools across the country, circle time is usually for reading stories, playing games or show and tell.

But this is no ordinary school—and these are no ordinary kids.

Daposka Ahnkodapi (“Our School” in Osage) is a private school serving Osage children from six-weeks through 8th grade that was established by the tribe to strengthen and preserve its language and culture through education.

As circle time begins, Pratt speaks to his students in Osage, making announcements, asking questions and praising them with gentle humor, as they reply politely in unison with the pride and solidarity that comes from speaking their own language. On this day, they conclude by singing the old Redbone hit, “Come and Get Your Love,” entirely in Osage before scattering back to their classes to finish their assignments for the week.

In one class, students are working on science assignments. Across the hall, others listen to language lessons on headphones—following along in the Osage alphabet. In the infant room, babies and toddlers are busy having playtime with their caregivers, who speak to them using every day Osage words and phrases.

“We are strengthening their identity as Osages,” says Pratt, the Osage language teacher and curriculum specialist, who spent decades learning the language so he could teach the next generation. “And the way to do this is to indigenize their education because our language is critical to our survival and who we are as a tribal nation.”

Together, these students, their teachers and the staff are part of the vanguard in the tribe’s mission to save the Osage language. Once nearly extinct, efforts to restore their language–including the development of their own written alphabet–has become one of the most moving and powerful stories of tribal language revitalization in U.S. History.

Through the development of its school, curriculum and early childhood education programs, as well as community, high school and college-level classes, the Osage Nation has invested millions to rebuild its language through education—starting with its youngest members.

Patrick Martin is the superintendent of Daposka Ahnkodapi. A member of the Osage Nation, his career as an educator began at a public high school in Tulsa before becoming a pre-K-8 administrator. But when the opportunity to work for his tribe in helping establish its own private school arose, he wanted to be a part of an historic effort to build an educational institution that would create permanency for Osage language and culture.

“This school has such a great family environment and we have a lot of siblings, which is wonderful, because they can learn together,” says Martin. “I want to pass [language and culture] on to them, because if we don’t, it’s going extinct.”

Beginning at six-weeks-old, these children are in an educational ecosystem designed by and for the Osage people to protect their own distinct cultural heritage from further loss.

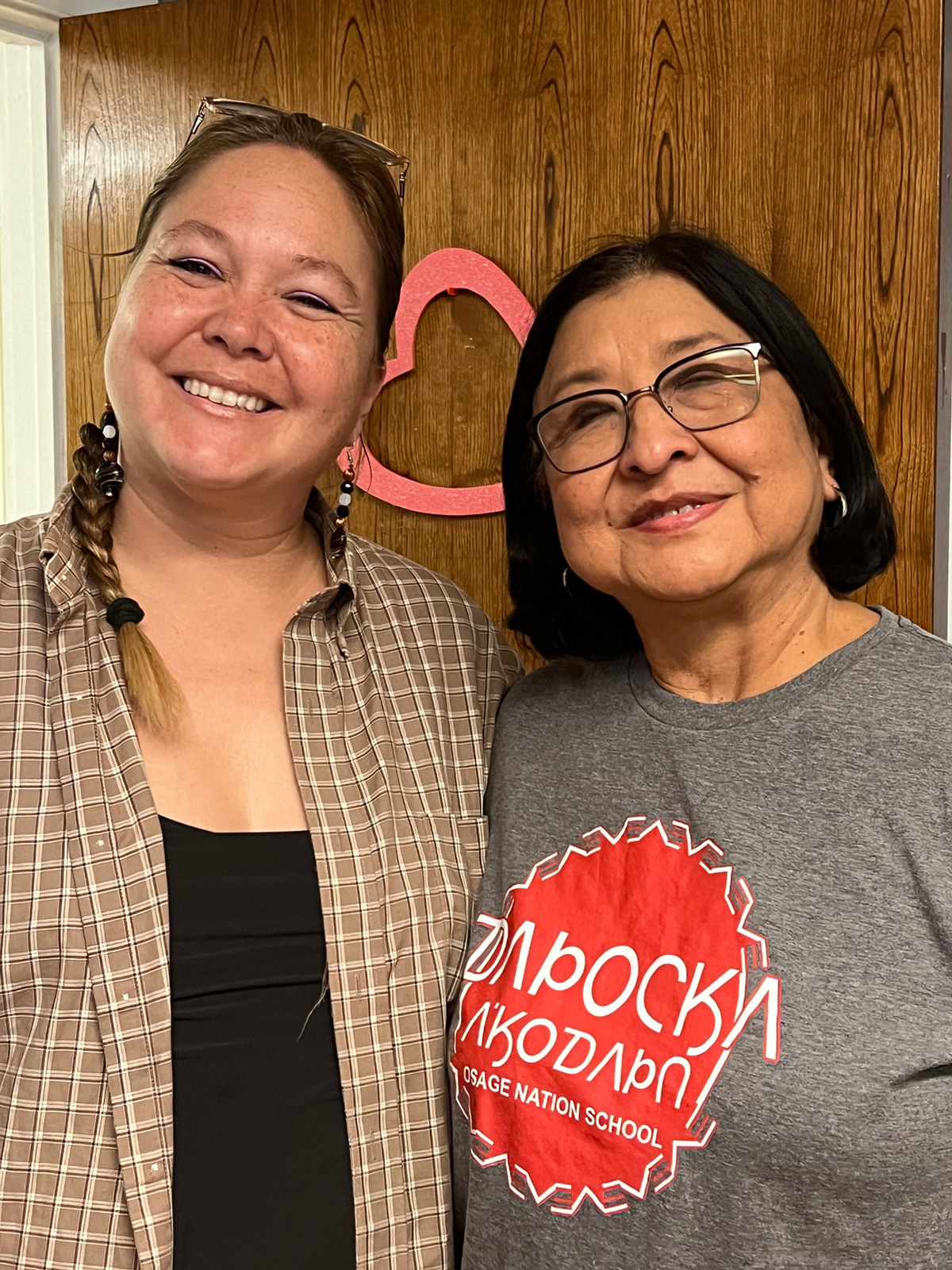

“We talk with our babies and children using every day words and terms of endearment because it’s the natural way to instill language acquisition from the earliest age possible,” says Denise Keene, an Osage elder who has worked with the tribe’s early childhood program for over 40 years.

“We know that if a child is surrounded by the language from six weeks to age 14, as they are here, it becomes permanently wired into their brains—because it has to build up over time. And that’s the goal here: to create a generational chain of speakers who can pass it on to future generations.”

Not long ago, speaking Osage and singing tribal songs in a school setting would have been nearly unheard of—and was, in fact, forbidden for decades—as the government launched its crusade to enforce English-only at the expense of tribal cultures.

Along with hundreds of other tribes across the country, the Osage are in a race against time to claw back their languages from the abyss. For those already lost, many tribal language experts and historians lament the profound loss not only of the languages themselves, but also the histories, scientific achievements, stories, songs, prayers, poems and human knowledge that were contained therein.

For many, it is a loss on the scale of the Great Library of Alexandria, leaving many Native communities with only tiny shards of words and phrases. Like scattered bits of DNA, reconstructing a lost language to full fluency is nearly impossible once it’s gone.

A Staggering Achievement

As a boy, Vann Bighorse can recall hearing the language spoken on the tribe’s reservation in northern Oklahoma. His memories of dances, ceremonies, prayers, songs and feasts were all informed by the Osage language, which has been central to the tribe’s distinct cultural identity for thousands of years.

“At our I’n-Lon-Schka [ceremonial dances], I’d hear them talking in Osage when I was little and I was curious about what they were saying,” says Bighorse, now 65. “At that time, our language was in wider use and we still had first-language Osage speakers. But many of us who were younger were either not fluent or had limited fluency.”

In the 20th century, Osage, along with many other Indigenous languages, went into rapid decline due in part to the deleterious effects of English-only government boarding schools. As the older generations began dying off, English became the dominant language at home and in school districts in Native communities across the country.

“Our first-language elders were gone in the blink of an eye,” says Bighorse. “So our tribal leadership really stepped up and made language preservation a top priority for our government, including a provision in the Osage constitution, creating a cabinet position and setting up a permanent budget, staff and other resources to protect this vital part of our culture.”

Today, Bighorse is the Secretary of Language, Culture and Education for the Osage Nation and oversees one of the most aggressive tribal language preservation programs in the United States.

But the origin story of how the tribe pulled its language back from the precipice begins with a small, dedicated group of tribal members who worked diligently for years to preserve and teach their language with small, informal classes in homes, libraries and other locations across the reservation.

One of them was master Osage language teacher, Dr. Herman “Mogri” Mongrain Lookout. Now 82, Lookout is one of the last surviving full-bloods in the tribe and was the founding director of the Osage Language Program from 2004 to 2016. Having spent over half a century studying and teaching, he worked tirelessly with tribal language experts and fellow speakers to delve deeply into the words and their sounds to standardize meanings and spellings.

This proved to be an enormous challenge, since Osage words had been written phonetically in the English alphabet for decades, which led to confusion and a lack of consistency for teachers and students alike.

Thus, it was Lookout’s work on the creation of a standardized Osage alphabet in 2006 that will be his lasting legacy. A staggering achievement in the field of world languages, the development of a stand-alone orthography has strengthened and codified the Osage language for all time.

“Many tribes still struggle to try and reproduce their words using the Latin alphabet because it doesn’t really address certain unique sounds in Indigenous languages,” says Pratt. “Mogri knew that to reproduce an Osage sound as it is meant to be understood in writing, it became necessary to create our own alphabet to eliminate confusion and create a consistent writing system that will make our language more likely to survive.”

Understanding the critical role of technology in creating new language learners, in 2016 Lookout and Pratt championed the effort to include the Osage alphabet in The Unicode Standard—the universal character encoding system that supports text in the world’s written languages. With Unicode, the Osage alphabet can now be used on any smartphone, tablet or device so that students of any age can read, do homework, send texts or use search engines in their language.

“Tribes have their languages, their cultures and their land base,” says Bighorse. “These are the sovereign pillars of Indian nations and without them you are vulnerable to extinction and that’s part of what makes our language initiatives so vital to our way of life.”

An Ancient Cacophony

Though estimates vary on the exact number of people in the Americas prior to the arrival of Columbus, it is now believed that there were approximately 50 to 60 million inhabitants in the Western Hemisphere, speaking more than 2,000 distinct Indigenous languages—a cacophony of ancient voices, many of which are now mostly extinct.

In North America alone, there were approximately 700 languages spoken by an estimated 7 million people at the time of Contact (referring to Columbus/1492), according to Cherokee anthropologist Russell Thornton, who specializes in pre-Columbian demographics at UCLA.

Some languages, like Shoshone (part of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family), stretched from Idaho into Mexico largely due to thriving and sophisticated commerce routes in the Great Basin of the western United States, as well as the seasonal hunting and fishing patterns by the tribes.

After Contact, however, the cumulative effects of centuries European encroachment resulted in a dramatic depopulation over the next 400 years.

By 1900, there were only 237,000 American Indians remaining in the United States, according to the U.S. Census—the lone survivors of four centuries of genocide, disease, forced removals and a raft of government policies designed to extinguish tribal cultures. As millions disappeared, so too did their languages.

Today, according to the 2020 Census, the Native population in the United States has rebounded to approximately 10 million. Even so, the ongoing loss of tribal languages remains a major concern among the nation’s 574 federally recognized tribes. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), there are roughly 167 Indigenous languages remaining, but experts estimate that by 2050 only about 20 will remain.

Thus, there remains an ancestral, sacred belief among the tribes that their cultures are inextricably tied to their words—including their songs, ceremonies, cultural concepts, spiritual practices, foodways, oral histories, naming babies, and familial clan systems, which form the structure of nearly every tribe in both the United States and Canada.

“Language is culture and culture is language,” says Bighorse. “Without it, who are we?”

Wazhazhe Always

With its reservation in northern Oklahoma encompassing nearly 1.5 million acres, today the Osage Nation has approximately 25,000 members and refer to themselves as the Wazhazhe, or ‘Children of the Middle Waters.’ Having originated in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys 2,700 years ago, their ancient language is a part of the Western Siouan language group known as Dhegihan, which also includes Kansa, Quapaw, Omaha and Ponca.

In ancient times, all of them were originally part of one tribe known as the Hunka Tsezho (Earth and Sky People) that originated in the Ohio River Valley before eventually migrating west and breaking up into different bands and developing their own dialects, according to oral histories and archaeological evidence.

In 1872, during the peak of the Indian Wars, they were forced by the U.S. Government to relocate to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma—one of the few tribes that were able to buy their own lands, giving them mineral rights and other protections as landowners. After oil was discovered on their lands in the 1890s, however, they subsequently became the wealthiest people on earth. But their success also led to the targeting and murder of tribal members for their oil rights by non-Native swindlers and local businessmen, which was recently depicted in the Oscar nominated film, Killers of the Flower Moon.

Through it all—wars, pandemics, removals, boarding schools and other policies aimed at forced assimilation or eradication—the tribe stubbornly clung to their ways, refusing to give up the one thing is most precious to them: Their language.

Now, armed with a written alphabet and an infrastructure built for longevity, the Osage are turning the soil, so to speak, on a new generation of language learners.

For parents like Electa Hare and Ryan Redcorn, the decision to send their three young daughters to Daposka Ahnkodapi was an easy decision.

“We really wanted our kids at the school so they could learn and be immersed in the language,” says Hare, who is a member of the Pawnee Nation, though her children are enrolled Osages. “Our kids are 13, 11 and 8, and we’ve been at Daposka since it began, with our youngest starting at three-months-old in the infant class. It has paid off in abundance, because our kids are thriving there.”

For Superintendent Martin, Daposka Ahnkodapi represents a continuum of the Osage way of life.

“As an Osage, when I look at these students, my hope is that they will eventually become teachers themselves,” he says. “Because if we keep doing this, we’ll eventually win that race.”

Suzette Brewer

Suzette Brewer is a writer and producer specializing in federal Indian law and social justice issues, having written extensively on Indian Child Welfare, the Supreme Court, violence against Native women, education and environmental issues on Indian reservations.

She has written for National Geographic, The Dallas Morning News, The Denver Post, Scripps News and many others. Her published books include Real Indians: Portraits of Contemporary Native Americans and America's Tribal Colleges; and Sovereign: An Oral History of Indian Gaming in America.

She is the 2015 recipient of the Richard LaCourse-Gannett Foundation Al Neuharth Investigative Journalism Award for her work on the Indian Child Welfare Act; a 2018 John Jay/Tow Juvenile Justice Reporting Fellow for reporting on juvenile justice in Indian Country; and a 2020 recipient of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Grand Prize for the documentary A Broken Trust for Scripps News Service. She is a member of the Cherokee Nation and is from Stilwell, Oklahoma.