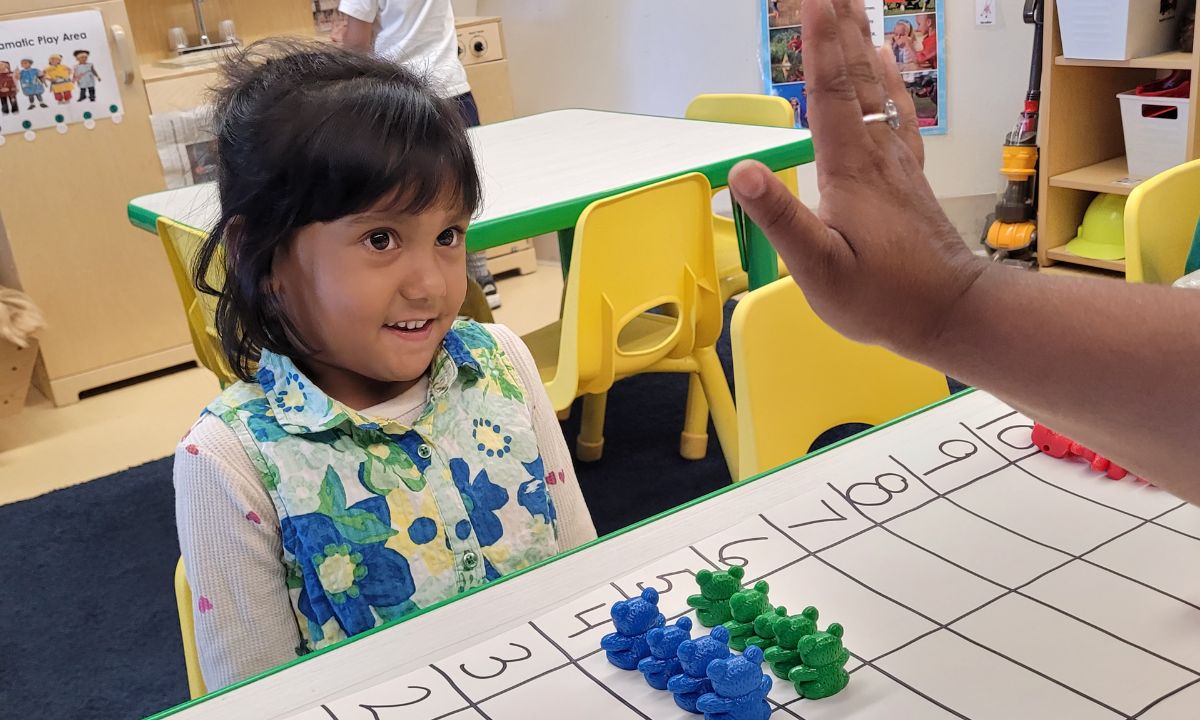

Preschool teacher Emily Johnson counts the row of green bear figurines Mayeda Alan, 4, has set on a table at the George Forbes Early Learning Center in East Cleveland, Ohio.

“How many do you have? One…two..three…four,” Johnson says, before they place another bear in the row. “What if we add more? What comes after four?”

Johnson smiles when Mayeda replies with “five.” The stealth math lesson is working. Mayeda “added” a bear and is starting to understand, in subtle ways, the very early basics of addition.

“They think it’s play,” Johnson said, stepping away to let Mayeda line up bears on her own.. “They don’t always understand that they’re actually learning things.”

Math lessons like this, disguised as a fun activity playing with colorful bears, should be a regular part of preschool, math experts say, especially as older students across the U.S. struggle with math after the pandemic.

But such lessons are a rarity. Preschools devote just five percent of time to math skills, researchers reported earlier this year after observing 77 preschool classrooms in seven states — Arizona, California, Massachusetts, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio and Virginia.

The researchers from four universities also found math instruction between 2018 and 2020 rarely went beyond the most basic math skills, like learning numbers, counting and identifying shapes, which are important for students to learn, but stop short of what most four-year-olds can do.

“They’re getting hardly any math,” said Michelle Mazzocco, a professor at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development and co-author of the study.

While some may see doing basic counting for a few minutes a day as the right thing for most preschoolers, Mazzocco and other national math advocates say it’s a lost opportunity.

With falling scores on math tests such as the international Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests – which dropped between 2018 and 2022 by two-thirds of a year’s worth of learning – teaching basic math in preschool, if done well, can make it easier to understand advanced lessons later, Mazzoco said. When presented as games or play, even four-year-olds can learn basic concepts behind math tasks like measurement, geometry, addition and subtraction.

“Some of those children who struggle with math are struggling because they got off to a slow start,” Mazzocco said. “That can be diminished.”

“We need to make sure that preschoolers have more opportunities to engage their natural inquisitive interest in math, to do so regularly and frequently in developmentally appropriate ways,” she said.

Latrenda Knighten, the president-elect of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, agreed students can learn math concepts at a young age and preschools should teach much more of it. She doesn’t expect a math learning revolution similar to the “science of reading” across the country, but wants math to be a priority, even in preschool.

Though there are vigorous debates over how preschool gains in all subjects fade over time, Knighten said. But if students learn more math early on, and kindergarten and later grades build on that knowledge, not just re-teach it, scores should go up, she said. Preschool math also provides an early start on learning critical thinking, problem-solving and recognizing patterns that pays off later, she said.

“You hear a lot about literacy, literacy, literacy,” said Knighten, a former elementary school math coach. “In an ideal world, you maybe turn those wheels and give math the focus that we’ve had on reading for so long.”

Historically, preschool math has been a low priority, both because of the traditional focus on reading but also because preschool is often viewed as child care or play-based more than an academic program. States don’t require preschool and few pay for it, so just 35 percent of four year olds nationally attend preschool, according to the National Institutes for Early Childhood Research at Rutgers University.

There’s also no national consensus on what students at that age should be taught. The nation’s last attempt at setting national education standards, the Common Core movement, faced opposition to its kindergarten through 12th grade standards and skipped preschool altogether.

Even the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics promoted math skills starting in kindergarten from 1980 to 2000, before adding preschool in 2000.

The council and many states now have specific recommendations about what preschoolers should learn about numbers and shapes and measurement.

Consider counting, for example. Counting can be just memorizing and reciting a list of names assigned to each number. But the council and states also want preschoolers to learn that each number stands for a real quantity of items. They can be taught that each item should be counted once — not a few times or counting several items as one — which is a common mistake four-year-olds can make.

They can also be taught that the count of one group can be more than or less than the count of another.

Doug Clements, a professor at the University of Denver and co-author of the highly-regarded Building Blocks preschool math curriculum, said it is easy to underestimate what preschoolers can learn.

“There’s a common misunderstanding that in preschool you learn to count, then in kindergarten you count higher, and then in first grade you can learn arithmetic,” he said. If you give students a narrative, a story behind a problem, he said, and let them use objects to see things physically, they can understand math concepts well.

“People think that arithmetic is a vertical – a three, then a plus sign, two, bar under it, then fill in the numeral — which is not what I’m talking about,” he said.

Teachers can ask four-year-olds, for example, if they have five toys and give a friend two, how many they have left.

The colored bears in Johnson’s class, a common tool for preschools, offer a chance to show, without any lecture or worksheets, that objects can be sorted by color or size, that a row of six bears, for example, is larger than a row of four bears and that “adding” another bear to a row changes the number to a higher one.

It sounds simple, but teachers need to be intentional about how they handle “play” like this, Knighten said.

“It takes the teacher understanding what’s happening and knowing the right questions to pose to student,” she said. “Maybe ask them, ‘What can you tell me about how you’ve arranged these bears or these cars or whatever they’re playing with? Do you have more of one than you have the other? How do you know you have more? How can you show me?’ And that’s not even bringing out paper or pencil, it’s just understanding the math that a child at ages two, three or four is capable of understanding and how to provide opportunities for them to explore those things.”

The counting bears are one of dozens of toys and games packed into the math closet at the Fairmount Early Childhood Center in Beachwood, Ohio, just a few miles from Johnson’s Head Start class.

There, students count off jumping jacks and toe touches to reinforce quantity. Children at one table glue decorations to printouts of the number one to reinforce how the number looks. In another classroom, three-year-olds pick through a box of different-colored blocks of different shapes and line them up in rows by shape and color, counting how many they have placed in each row as they go.

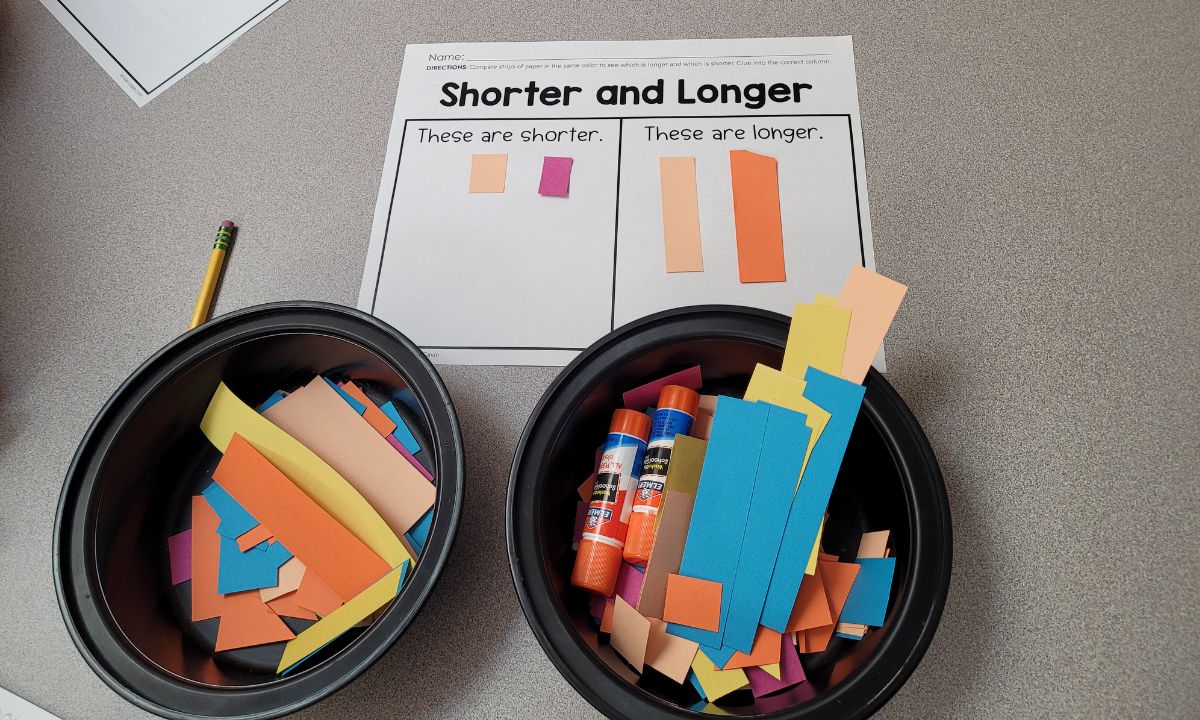

Teacher Rosanne Stark guides students nearby in the earliest stages of another math skill — measurement. Today, three-year-olds pick between shorter and longer rectangles of colored paper and glue them to a sheet under columns labeled “shorter” or “longer.”

“Would you say that’s on a long strip or a short strip?” Stark asks a student. “Long. Good job. So we’re going to glue it on.”

Clements said comparing lengths with activities like this is a good start.

“Then we move on to actual measurement, which is assigning a number to the length of something,” he said. That can happen first by attaching several, say five, blocks together to see if something is longer or shorter than five blocks, then “adding” or subtracting blocks to the right size.

“They can show you in the count of cubes,” he said. “It’s a very concrete measurement. It’s very easy to understand conceptually for kids, because it makes sense to them.”

How much impact preschool math has, though, is unclear. Researchers can point to multiple studies showing preschool math leads to better math performance in kindergarten and in elementary school, sometimes as late as eighth grade. But as with preschool overall, other studies show students taking preschool math don’t end up further ahead than other students in later grades. This so-called “fade” plagues most debates over whether preschool is worth the effort or cost.

Tyler Watts, an assistant professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College who is researching the effects of early math, said advantages sometimes nearly vanish by fifth grade. He and others are trying to figure out why.

“I don’t think it’s totally clear, to be honest with you,” he said. “I think it’s a hard problem to figure out.”

While he’s still a supporter of preschool and preschool math, Watts believes — like Mazzocco and Knighten suggested – that it can be the first of many steps in improving math lessons over several years.

“If the goal is improving, say, math achievement in grade eight, I think you’re going to need to work on that all the way from PreK through grade eight,” he said. “I don’t think PreK is going to work as kind of like a low-cost silver bullet for that problem.”

There’s another challenge to making preschool math better and more common — preparing teachers. Knighten said that in her time as a math coach in Louisiana, she found many gravitate toward teaching reading because they thought they were “bad at math” when they were in school and view it as an ordeal, Knighten said.

That’s why the council partnered with the National Association for the Education of Young Children this year to offer preschool math webinars for teachers on topics like Routines and Games to Illuminate the Big Ideas of Number Sense and Developing a Positive Math Mindset with Games, Books, and Technology for Young Learners.

“If we actually provide teachers with more confidence in their ability to teach mathematics to students,” Knighten said. “Then, of course, that means that they’ll spend more time on those activities with students, and students will actually get more of those beginning, foundational experiences.”

Patrick O'Donnell

Patrick O’Donnell is a correspondent at The 74, covering the impact of the pandemic on America's education system.