When she taught third grade in Houston, Summer Robinson invited a friend, a female mechanical engineer at Chevron, to visit her class. She wanted to introduce students, especially girls, to a STEM practitioner who didn’t conform to the socially awkward stereotype in popular culture.

“She communicates really well, and the kids just loved it so much,” Robinson said. “I don’t think they totally knew what an engineer was, but they understood that they help build things.”

Such exposure can help schools overcome gender stereotypes that form not long after children start school, according to a new international study from the American Institutes for Research.

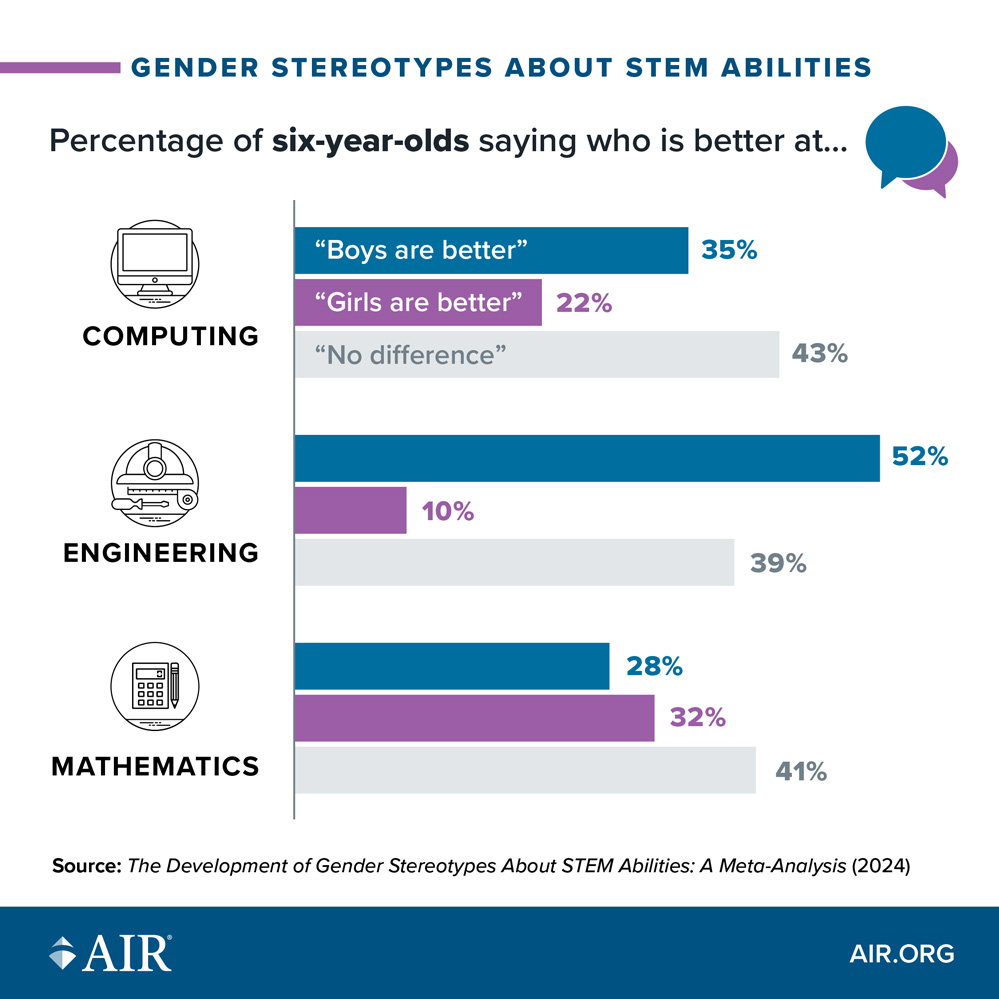

Based on a review of nearly 100 studies from 33 countries, the analysis shows that by age 6, kids already perceive boys to be better than girls at computer science and engineering. Among girls, such beliefs only grow more entrenched over time.

Without efforts to address those perceptions, girls might turn away from “fast-growing tech fields like artificial intelligence,” said David Miller, lead author and a senior researcher who started the project five years ago.

Released Monday, the findings, he added, have “downstream implications for thinking about what high school course electives girls might decide to choose, what majors they might go into and then later, the workforce.”

Recent data from Code.org, a nonprofit that advocates for computer science in K-12, shows that girls’ participation in computer science drops off as they get older. In the elementary grades, girls comprise about half of those enrolled in a foundational computer science course. But participation falls to 44% in middle school and 33% in high school. Experts see promising increases in women pursuing STEM fields, but Miller recommended even greater efforts to expose young girls to opportunities in computer science and clear up misconceptions.

One study cited in the paper found that roughly three-fourths of young children think that engineers work on engines and repair cars. Only a third said that engineers design things.

Just as kids show an early bias toward boys in specific STEM fields, they also develop stereotypes that favor girls in reading and writing. By age 8, students think girls are more verbally gifted, the study found.

Julie Flapan, who directs the Computer Science Equity Project at the University of California Los Angeles, sees opportunities to encourage boys’ literacy development through their passion for gaming.

“With technology, there’s so much storytelling that goes on in creating video games. It’s not just passively sitting behind a screen, but actually has a lot of creativity, collaboration, problem-solving,” she said. “When we focus on those elements of computing, it is really engaging for a lot of kids.”

For years, the project has offered training workshops for teachers, and over time, participation among K-5 teachers has increased. About 45% of the teachers who attended workshops last year were elementary teachers.

“Teachers play a huge role. School counselors also play a very big role as gatekeepers for who gets put into a computer science class,” Flapan said. Parents often enroll their sons in coding camps or encourage them to join robotics clubs, giving them a leg up over their female peers. “Teachers will see that these boys are really excelling in computer science and say, ‘See, they’re just born to do it.’ Then a girl walks in and thinks ‘Well, that doesn’t look like a space for me.’”

Efforts to increase computer science and engineering opportunities for girls at the elementary level, however, often depend on educators who have extra time and interest in the topic, said Robinson, now a doctoral student at the University of Houston who focuses on gender disparities in computer science. At Sanchez Elementary, the high-poverty school where she taught previously, several girls attended an afterschool robotics program organized by a social worker. But it didn’t last long.

“It’s really hard to implement that stuff at the elementary level without a class because so much pressure is pulling you in different directions,” Robinson said.

Some previous studies suggested that in early childhood and the elementary grades, children viewed boys as more math inclined than girls, but Miller’s study showed that children think boys and girls are equally capable of mastering the subject.

The analysis found differences in how children perceive specific science fields. Students thought boys would do better in physics, while females would be stronger in biology. That’s why Miller thinks researchers should focus on the STEM fields where stereotypes are the strongest, rather than looking broadly at kids’ attitudes toward math and science.

“Computer science, engineering and physics … should instead take center stage in future research on children’s gender stereotypes about STEM abilities,” he wrote.

It’s also important to recognize progress, said Talia Milgrom-Elcott, founder of Beyond 100K, a national network focused on building the STEM educator workforce.

In 2019-2021, for example, girls made up at least half of the enrollment in Advanced Placement computer science courses at over 1,100 schools nationwide — up from 818 schools the previous year. The Code.org report also shows that when girls take the AP computer science exam, they earn a score of 3 or higher at rates similar to boys, 61% to 65% respectively.

And over the past decade, women entering STEM fields grew by 31%, compared to 15% for men, according to the National Science Foundation.

“I want to know that all the deliberate efforts we’re making are adding up,” she said.

Linda Jacobson

Linda Jacobson is a senior writer at The 74.