Two years ago, Minnesota outlawed most suspensions and all disciplinary seclusion of very young pupils in schools. An outgrowth of an effort to curb police abuses In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, it was a change that advocates for children with disabilities and students of color had long sought.

But now, bills before the state legislature would roll back these reforms and again allow schools to dismiss children in kindergarten through third-grade.

Three measures under consideration would strip a prohibition on “disciplinary dismissals” — the removal of children from schools — in grades K-3, loosen the definition of student behavior meriting exclusion from the classroom, end a requirement that schools try non-exclusionary strategies before dismissing a child and let schools once again punish youngsters by denying or delaying their access to lunch and recess.

A separate bill would overturn a ban on seclusion for K-3 students — the practice of confining a child in isolation. Some people believe seclusion should be an option when a child’s behavior is out of control. Others call it punitive and cruel, particularly when used on very young children.

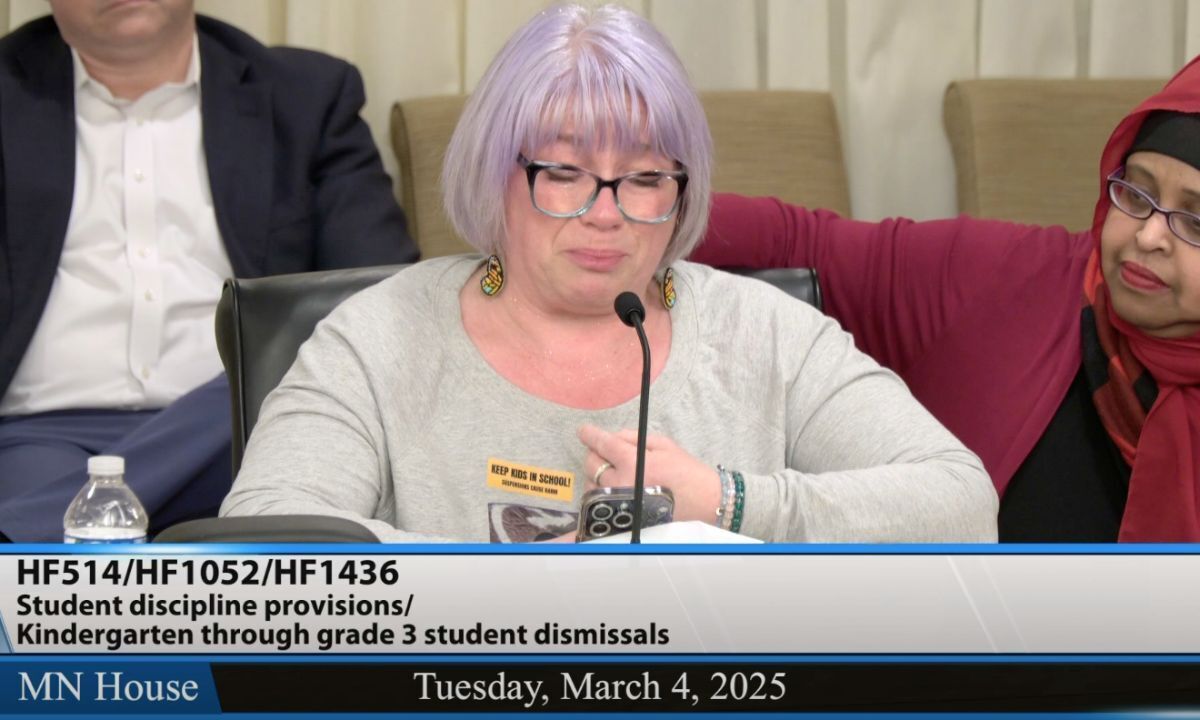

That split was evident in testimony at a recent state House of Representatives hearing on the legislation. Sitting on opposite sides of a windowless Capitol hearing room, the witnesses took turns describing starkly different realities.

Principal of Jeffers Pond Elementary in the affluent, suburban Prior Lake-Savage Area Schools, Patrick Glynn testified that suspensions provide “the gift of time” so staff can “allow for healing” and create a “re-entry plan” for the student in question.

Minnesota Elementary School Principals Association President Lisa Carlson, who oversees a school in another prosperous Twin Cities suburb, said a suspension can send a strong signal to a parent in denial about a student’s issues: “For some families, the only way to truly recognize the severity of a situation is to be inconvenienced by it. When a child is suspended, parents are forced to stop, pay attention and take action.”

But parent and educator Ali Alowonle told lawmakers that suspension taught her child the wrong lesson. “She was told that she could not come to school because a police officer had to determine if she were a danger,” Alowonle said. “She began to hate school and refused to go. Suspension broke my kid’s trust in school and adults there.”

Parent Susan Montgomery broke down describing her son’s suspension setting off a destructive cycle. “Now, at 20, he is trying to rebuild his life,” she said, pausing to choke back sobs. “He is taking computer class, participating in healing circle, Bible study, working as a janitor and attending recovery groups — but all behind bars.”

However and whenever lawmakers vote on the bills — they may be standalone legislation or wrapped into an omnibus spending package – they will resurface longstanding racial and demographic divides.

Minnesota has long had nation-leading racial disparities in education, with a teacher corps that is more than 90% white and an increasingly diverse student body. Its schools also have a long history of suspending and expelling non-white students and children with disabilities at much higher rates than their white, nondisabled peers.

In 2017, the state Department of Human Rights entered into a settlement with 41 school districts and charter schools that were found to have suspended and expelled non-white children and those with disabilities at disproportionate rates. A 2022 report from Solutions Not Suspensions, a coalition of advocacy groups that has campaigned for 10 years for laws requiring schools to stop disciplinary practices, found that children of color received 79% of exclusionary discipline despite being 49% of the student body during the 2018-19 school year. Children with disabilities made up 14% of students but received 43% of suspensions and expulsions.

The agency noted that when the reason for discipline was subjective — e.g. “disruptive behavior” or “verbal abuse,” versus bringing a weapon to school — the disproportionality skyrocketed.

Armed with these numbers, advocates got a break in 2023, when Democrats gained power in both legislative chambers and the governor’s office. They enacted laws outlawing the use of dangerous prone restraints by police officers stationed in schools and dramatically narrowed schools’ authority to dismiss children.

But limits on police authority in the wake of Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis officer had divided Minnesotans along both partisan and geographic lines, with city residents saying they were long overdue and rural residents largely opposed. In 2024, with an election looming and the support of rural Democrats feared to be softening, the Democratic-majority legislature reversed the ban on prone restraints.

The 2024 election left the state House evenly split, with equal numbers of lawmakers from each party set to take office. The late discovery that a Democrat did not actually live in the district where he was elected gave Republicans a one-vote majority until a March 11 special election likely restores the 67-67 split. They immediately started working to try to roll back policies enacted by the Democrats in 2023 and 2024.

Support for the discipline reforms passed in 2023 had been weak among rural Democrats. Now, advocates fear that the rollbacks being proposed by the Republicans could clear the state Senate, which has a one-vote Democratic majority. Advocates fear Democratic Gov. Tim Walz would not veto the measures.

Kate Lynn Snyder is a lobbyist for Education Minnesota, the state’s teachers union. Speaking in opposition to the changes, she reminded lawmakers that it is still legal for teachers to remove students from classrooms. Schools can send children home for less than a day, impose an in-school suspension or send a child to a sensory break room. When there is an ongoing, serious safety threat, expulsion is still possible.

“The largest complaint I hear about school safety from my members is that when our teachers call administrators to send someone to their office, no one is answering the phone,” she said. “That might be because of the perception that their hands are tied, or it might be because of the educator shortage, but either way teachers, like students, are not getting the currently allowed supports that they’re asking for.”

The state Department of Education also opposes the changes. At the hearing, lobbyist Adosh Unni described resources the agency has made available to schools interested in changing their approach to discipline.

Matt Shaver, a former teacher who is policy director of the advocacy group EdAllies, urged lawmakers not to return to allowing schools to withhold or delay lunch or recess because of a student’s behavior.

“I took a lot of recess away from kids during my decade in the classroom,” he said. “I used this tool when students didn’t finish their homework or worksheets or weren’t focused in class. My line was, if you’re going to be playing during class time, you’ll do class time during your play time. I thought I was pretty clever and delivering consistent logical consequences that would teach the behaviors I wanted to see for my students. In hindsight, I was wrong.

“This wasn’t an effective tool because the same kids missed recess over and over,” he continued. “Instead of keeping a kid inside for a punishment, my time with them would have been much better spent on the playground building that relationship that would have made it more likely for them to respect and listen to me as their teacher.”

Beth Hawkins

Beth Hawkins is a senior writer and national correspondent at The 74.