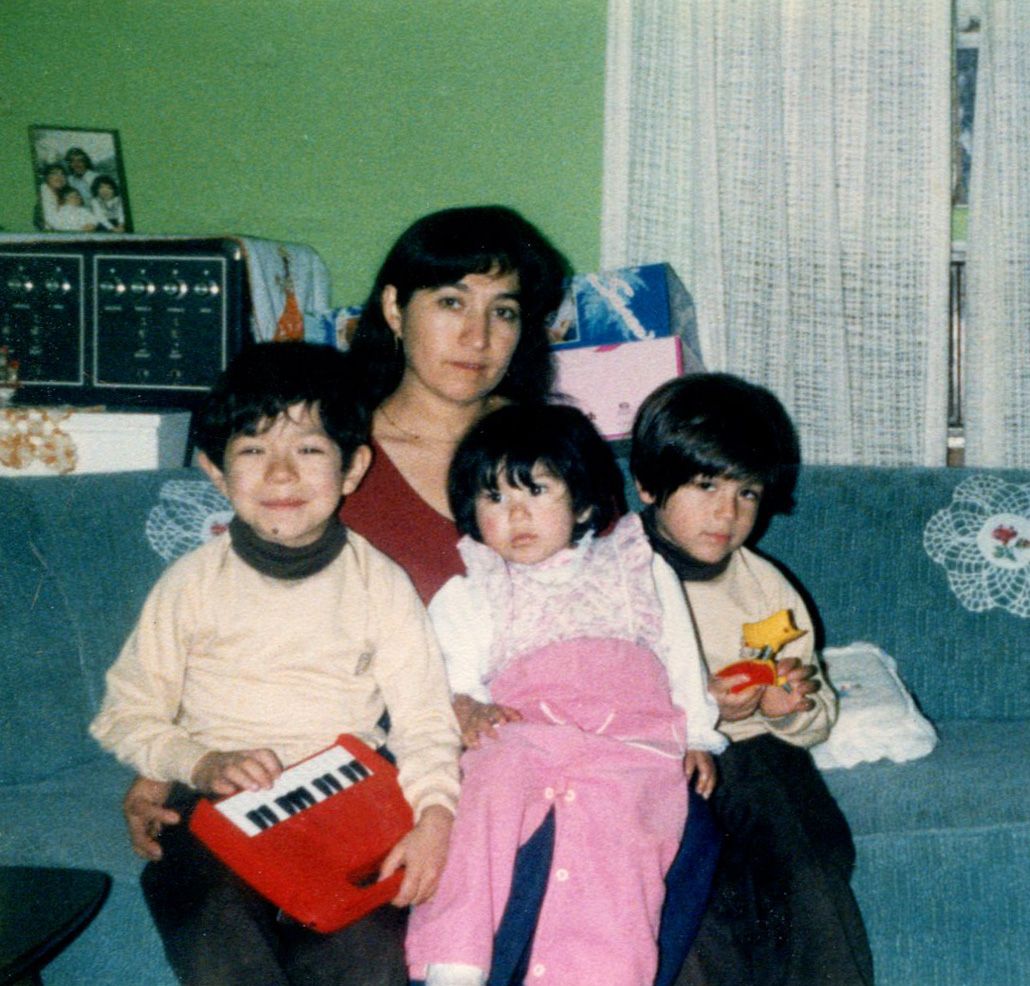

The son of farmworkers, Eric Guerra remembers tagging along with his mother while she picked figs for a dollar per 40-pound bucket and his younger sister knelt on kneepads nearby. Today, when Guerra takes his three-year-old son Javier with him to work, it’s not in fields but in City Hall.

When he was elected to the Sacramento City Council in 2015, Guerra says, “All of these memories were coming back to me.” Fatherhood still loomed in his future when he voted against the elimination of funding for before- and after-care. And he has continued to champion the issue of early learning in his city, organizing summits and designing family-friendly policies.

“Early childhood development drives racial equity and economic mobility,” Guerra says. “The children who get that early education have a head start in life.”

COVID’s economic fallout has strengthened his conviction. “Working women’s gains have been eradicated during the pandemic—especially women of color,” he explains. In Sacramento, a state capital with a great share of government employees and a considerable number of refugees resettled from Southeast Asia, the needs for child care are both deep and diverse.

- Easing up on the tickets. It might sound minor, but during rush hour, the most stressful time of the day, the last thing parents need is a parking ticket when they drop off or pick up their children. “They aren’t there for the free parking,” he notes. “Toddlers can’t check in by themselves.” Sardonically noting the harm done when men draft the policies, he explains how he expanded the window of time for leaving your car at child care from five minutes to fifteen.

- Understanding the cityscape. A technical assistance grant from the National League of Cities helped Sacramento develop a better understanding of the local landscape and to elevate early learning with decision makers and other stakeholders. This investment culminated in the City’s first Early Learning and Childcare Summit and to a new position in city government: Childcare Manager.

- Partnering to meet demand. The immigrant community represents a talent pool that can rectify the deficit in quality child care in Sacramento. The Child Care Law Center provides regular trainings with in-home providers to ensure they know their rights as providers serving their community. The organization’s child care coordinators assist them in obtaining licensure and running their small businesses, and supporting them in offering quality child care to their community.

- Learning from other cities. The Parramore Kidz Zone in Orlando, Fla. (itself inspired by the Harlem Children’s Zone) particularly inspired Guerra and his team. They have also been impressed by deliberate and careful collaboration among multiple agencies and community partners in Madison, Wis. and other cities.

👉 Inspiration and Adaptation: Helping Parramore’s Parents—and Their Children—Learn and Grow in Orlando

- Incentivizing a livable wage. When Guerra pushes for state subsidies to boost the wages of child care workers, he’s drawing from his own lived experience; his mom eventually earned her GED and transitioned from farm work to child care, which pays more, but only slightly. Eliminating a cumbersome permitting process for independent child care business owners allows them to reach sustainability and to afford better pay for their staff.

- Walking the inclusiveness walk. In light of his own personal story, it shouldn’t be surprising that Guerra makes it a priority to include diverse voices on his team. His chief of staff, Koy Saeteurn, is the daughter of refugees from Iu Mien tribe from Southeast Asia. (Read her story here.)

- Zoning for families. “You shouldn’t have to rely on luck when it comes to finding suitable care for your children,” Guerra says. He and his staff identify child care deserts and incentivize incorporation of centers into the design of new construction. “If it’s not in the design,” he asserts, “it’ll never get built.”

Making life better for young children in a city like Sacramento requires ingenuity and perseverance, and it is not an issue that generally wins elections—since those kids don’t vote. The sector, however, recognizes Guerra’s dedication, and in 2019, First 5 Sacramento gave him the High 5 Award for the Systems Improvement Affordable Quality Child Care, acknowledging his “leadership and advocacy for more accessible and affordable child care options.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.