The American Rescue Plan signed by President Joe Biden on March 12 contains a number of potentially game-changing policies for young children. These measures did not just appear fully formed out of thin air. They were set in motion before the emergence of Covid-19, before the Great Recession of 2007-09, even before the birth of many parents of today’s young children.

👉 Read more: American Rescue Plan: the United States Finally Invests Serious Resources in Our Children

Take the antipoverty provisions, for example. Researchers like Lawrence Aber have been exploring possible solutions for child poverty for decades. “Anybody who says ‘I did this’ is misrepresenting the reality,” says Aber, professor of psychology and public policy at New York University as well as co-director of Global TIES for Children. He credits a “community of inquiry” spanning academia and policymaking.

“It’s not one single study,” Professor Aber explains. “Knowledge accumulates over the course of many studies.”

Aber’s research journey began at Yale University in the 1970s, studying under Edward Zigler (1930-2019), a pioneer of applying developmental psychology to social policy and often credited as one of the main architects of Head Start. Back then, Aber was curious about the causes and consequences of child abuse, neglect and maltreatment.

“We didn’t know the extent to which economic insecurity was a cause of maltreatment,” he recalls, “or just a correlated factor.” This inquiry led to broader questions about poverty and violence. Over multiple studies, at least one inescapable conclusion emerged: poverty causes damage to child development by means of toxic stress. “It’s not just a matter of correlation,” he emphasizes. “It’s causal. This is true regardless of race, but it’s especially acute for Black and Latino children.”

The immediate history of the anti-poverty provisions in the American Rescue Plan devoted to young children dates back to December 2015, when Congress commissioned the National Academy of Sciences to “identify evidence-based programs and policies for reducing the number of children living in poverty in the United States by half within 10 years.”

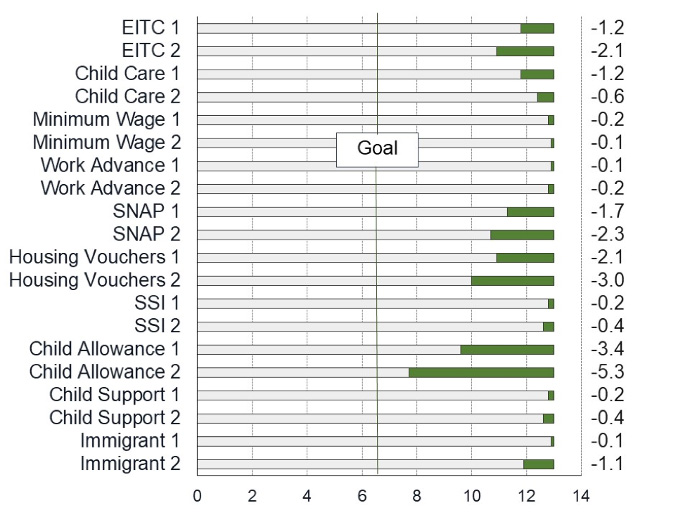

Generating ideas for how to cut child poverty in half is a bigger undertaking than any one discipline can manage, so National Academy convened a committee of 15 experts (including Professor Aber), who specialize in public policy, economics, child welfare, developmental psychology and medicine. The committee invited outside testimony from universities, think-tanks and other organizations representing diverse political perspectives. Two public information-gathering sessions informed their work, as did 25 policy memos. Four years in the making, the 600-page Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (2019) is a “consensus study report”—that is, it focuses on solutions that have come to be accepted by the research community.

👉 Download A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (National Academy of Sciences, 2019)

“Ethically, you can’t conduct rigorous experiments by taking money away from people, thank goodness,” says Aber, “but there are different ways you can test giving money to families with children.” To alleviate poverty, the government can issue tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which have been proven to have the added benefit of encouraging work. It can simply give away money—in the form of unconditional (no strings attached) or conditional (conditioned on certain behaviors such as school attendance) cash transfers.

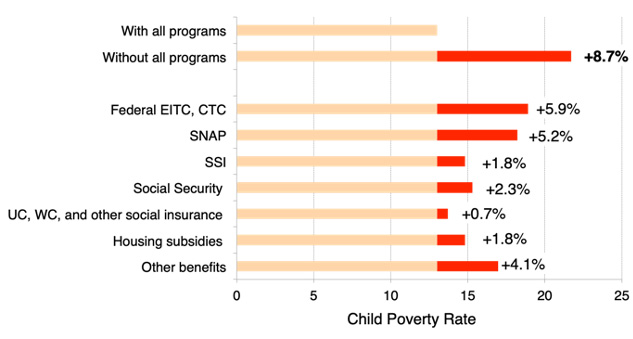

The commission adopted a set of “most of the above” recommendations (not conditional transfers, since there was not yet a sufficient evidence base on the efficacy). “If just one solution could do the trick,” notes Aber. “It would have been a simpler story to tell and an easier message for advocates to sell.” An expanded Child Tax Credit, functionally similar to a child allowance, is getting the most attention, but the expanded EITC, food and housing provisions all contribute to the ultimate goal of reducing child poverty by half.

Were it not for the pandemic, the Roadmap would have had a very different reception. It would certainly have influenced policy decisions, and elements of it might have appeared in legislation, but the pandemic’s massive job loss and economic fallout made the recommendations especially urgent. “Millions have been hurt through no fault of their own,” says Professor Aber. “That shifts the moral calculus.”

Reflecting on the lessons the American Rescue Plan offers for his field, Professor Aber notes that science is important, but it only gets us so far. “People nowadays like to say, ‘Do what the science tells you,’ but the most we can hope for is solutions that are inspired by and consistent with, not exclusively determined by, science.”

He also maintains that social sciences are not the domain of ideologues or those who expect tidy solutions. “If you want to work in this field,” he says, “you have to get used to the messiness of policy, where things like power and finances necessarily enter the mix.” He mentions a piece of advice Edward Zigler gave him when he was starting out in his career: We have to grow comfortable with acting in the face of ambiguity. “Yet, without the decades of research showing that poverty causes health and development problems and that child tax credits have been effective in reducing poverty, it is hard to imagine that the current legislation on child tax credits could have passed,” says Ellen Galinsky, chief science officer of the Bezos Family Foundation.

Professor Aber makes it clear that the American Rescue Plan isn’t the final end goal on reducing child poverty. Most of the provisions are set to last only one year. Efforts are needed to ensure that it’s effectively implemented and more research is needed on its impact and on other solutions like improving school achievement that build upon its accomplishments.

https://youtu.be/8S96UwXXo-s

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.