Just as Early Learning Nation showcases the ways families, researchers and grassroots nonprofits and organizations are building an early learning nation—one community at a time—our Community Cultivators series highlights how innovators across all sectors build and sustain global communities from the ground up. We hope the series inspires your own early childhood work.

“Music is very, very important for brain development,” Mary Gauthier states. “Especially when you sing together.”

Singer-songwriter and, now, author Gauthier (pronounced /go-SHAY/) isn’t a neurologist; she speaks from personal experience. “When I was a kid,” she recalls, “choir class was the one place where I knew I would have joy. Having kids sing together is a big deal. Especially troubled kids, especially kids whose families are on the rocks, which was my story. Especially kids whose parents are addicted, or mentally ill or on the edge of the world, in whatever way life has pushed them to the edge.”

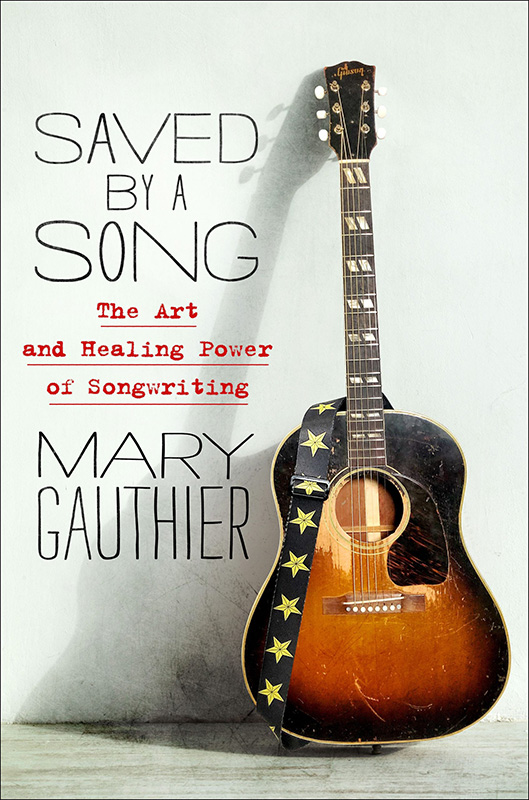

Her new memoir was published this month by St. Martin’s Essentials, just in time for her 60th birthday (and 31st year sober). Saved by a Song: The Art and Healing Power of Songwriting goes deep on the personal trauma, recovery, setbacks and triumphs of a music icon. As a songwriter, Gauthier has always been brutally honest, so it should come as no surprise that her book dwells on painful episodes from her past—most notably, blacking out on the cement floor of a holding cell after being arrested for drunk driving. “It was the bottom” she writes, “the end, but also, like all endings, it was a new beginning.” Even the more lighthearted moments come with traces of pain, such as her horrifically botched performance debut as “the only fat, old, Southern queer to play this New England folk open mic.”

Her new memoir was published this month by St. Martin’s Essentials, just in time for her 60th birthday (and 31st year sober). Saved by a Song: The Art and Healing Power of Songwriting goes deep on the personal trauma, recovery, setbacks and triumphs of a music icon. As a songwriter, Gauthier has always been brutally honest, so it should come as no surprise that her book dwells on painful episodes from her past—most notably, blacking out on the cement floor of a holding cell after being arrested for drunk driving. “It was the bottom” she writes, “the end, but also, like all endings, it was a new beginning.” Even the more lighthearted moments come with traces of pain, such as her horrifically botched performance debut as “the only fat, old, Southern queer to play this New England folk open mic.”

Reminiscing about this moment, she corrects my impression that open mic nights are hypercompetitive trials by fire for acoustic warriors. “Being good on stage is something that requires effort and time,” she says. “And you’ve got to be on stage to learn how to be on stage. And by that I mean you’re making a lot of mistakes.” There’s no better place for this to happen than a room of people who need to build confidence.

Along the way, she explores the mystery of songwriting—the passage of memory, emotion and experience from meandering chords to fully realized expressions that resonate with complete strangers. She re-creates the origin of her best-known song, “Mercy Now,” which is about her dying (adoptive) father but also God, country, war and the end of the world. “’Mercy Now’ started as a personal song, then it deepened. It became universal,” she realizes.

About the first single from John Lennon’s first solo album, she writes, “Raw, naked and brave, ‘Mother’ screamed what I most needed to hear: there was someone who’d been where I was and made it through to the other side, someone brave enough to articulate that experience.” The lesson for Gauthier: “Tell your story real, tell it true. Be courageous. Do not worry about who you will scare, who you will offend or if it will sell. Do this for your own soul, for your own salvation. Do it because you’re called to.”

Besides Lennon, Saved by a Song celebrates Bruce Springsteen, the Indigo Girls, Nanci Griffith, Ferron and more. Gauthier is especially drawn to songs that challenge accepted ideas of what songs are supposed to be about. “Sometimes when you speak your truth,” she says, “it collides with the cultural lie. And things can change when truths are told. Certainly, Johnny Cash did that, Willie Nelson did that, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, Steve Earle, John Prine, Lucinda Williams…. There’s taboo stuff we’re going to write about. We don’t write about it because it’s taboo; we write about it because we’re being asked to by… I don’t know what it is, inspiration, muses, we collide with it in our life.

Labels and radio stations routinely, adamantly discouraged Gauthier from releasing gay-themed songs like “Drag Queens in Limousines” and “Goddamn HIV,” but she persisted. In 2021, she marvels, popular culture embraces queerness. “Something has changed,” she says, “and that’s certainly part of the story that we’re living right now.”

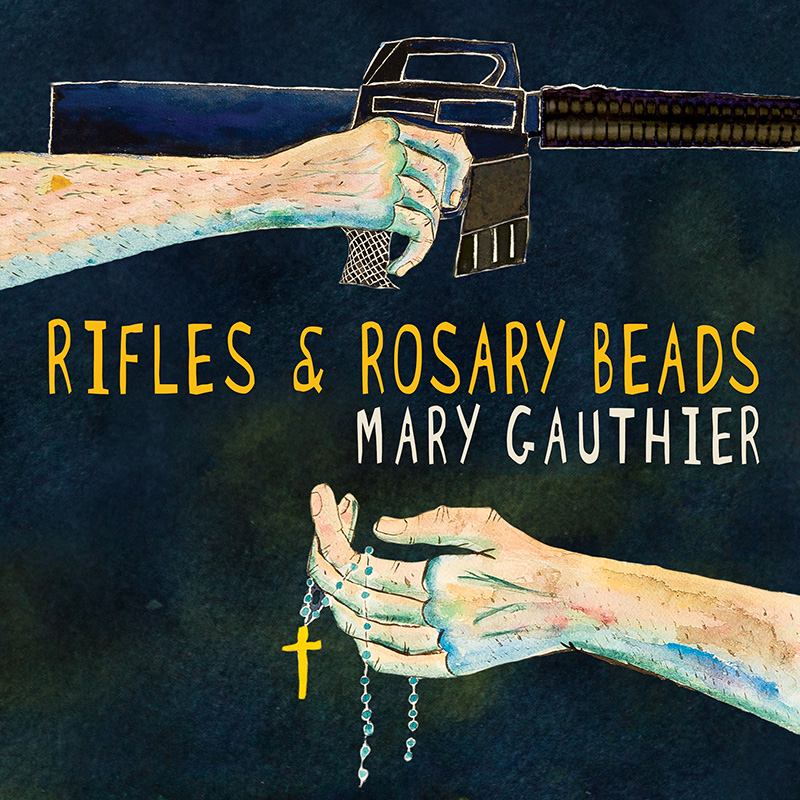

Many of the book’s most heartfelt moments introduce the reader to the Gulf War veterans she’s met through Songwriting with Soldiers, an evidence-backed program to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder. The songs on Gauthier’s 2018 album Rifles and Rosary Beads emerged from these workshops. A New York Times feature noted how they wrestle with “moral trauma, which happens when service members can’t reconcile what they’ve done with the people they believe themselves to be.” In a review for AllMusic, the critic Thom Jurek writes, “Gauthier and her collaborators look into the gaping maw of war, its trauma, isolation, rage and loneliness, to reveal the human faces and hearts of its witnesses. Popular music can do no more than this.”

Gauthier describes how she collaborates with veterans and their families: “Mostly, I’m creating a space for them to talk where they’re heard and seen, and safe. Not assessed. My questions lead to stories and the stories lead to questions. And before too long, something’s going to fall out of their mouth that’s a title.” These encounters yielded recordings and often-cathartic performances with soldiers who had never been on stage before. “When their song gets played in front of their peers,” she says, “they realize that other people are going through what they’re going through.”

Gauthier has continued to attend Songwriting with Soldiers workshops, disclosing that her favorite participants are the explosive ordnance disposal veterans. “I just love the bomb guys and their wives,” she says. “I’m so drawn to their stories. You’d think these would be some serious cats, but they are funny. Of course, it’s dark humor. It’s a coping mechanism.”

If she identifies with soldiers’ physical and emotional damage, it’s not out of morbid fascination. Even as she approaches 60, she probes psychic pain from her earliest years. “A child from an orphanage,” she says, “is a child that’s wounded.” The book takes the reader back to where it all began for Gauthier, a building in New Orleans bearing the inscription St. Vincent De Paul’s Woman’s and Infant Asylum. “Standing in the courtyard of this rotting institution,” she writes, “my mind blew open. Mysterious strangers connected by blood, far-off ghosts started to stir. My birth mother became real to me, a vulnerable, terrified girl with few choices— pregnant, unmarried, hiding in this institution with other girls like her—their agency taken away by shame, lack of money and oppressive cultural standards they’d failed to live up to. I had known my own pain for a long time, but that day I began to feel her pain too. In that moment, instead of simply feeling for myself, I began to feel the suffering of another screwed-up young woman: my birth mother.”

Gauthier notes that in 1962, almost all adoptions were closed adoptions. “Your original birth certificate is sealed, and it’s never, ever allowed to be unsealed,” she says. “The lack of information creates what I think is fairly called trauma. I needed to get the question mark out of the end of the sentence and find a period.” She doesn’t exactly find satisfaction or closure in the book, but, by virtue of pursuing answers, she works through some of the most difficult emotions in her 2010 album The Foundling.

Gauthier notes that in 1962, almost all adoptions were closed adoptions. “Your original birth certificate is sealed, and it’s never, ever allowed to be unsealed,” she says. “The lack of information creates what I think is fairly called trauma. I needed to get the question mark out of the end of the sentence and find a period.” She doesn’t exactly find satisfaction or closure in the book, but, by virtue of pursuing answers, she works through some of the most difficult emotions in her 2010 album The Foundling.

“I don’t feel like I’m carrying the rocks anymore,” she smiles, “I feel pretty light.”

Reflecting on decades of therapy and 12-step programs, Gauthier mentions Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs; read more here), saying, “My score went through the roof—a perfect catastrophe, a nuclear bomb.” She cites Gabor Maté and Bessel van der Kolk, who say the cause of addiction is trauma, and admits, “I didn’t even know I had childhood trauma until I started doing the adoption work and realized, Oh my God, yeah. A year in an orphanage without parents your first year, that’s traumatic. You were conscious, you were here on earth and you knew that you weren’t being held. So doing the work and then putting it into a narrative in a book I could see, Oh, that’s why I had the pain. That’s why I had the urge to kill the pain.”

She has spent her adult life trying to figure out how to turn that around. Today, she says, “I don’t have the big answers for the world, but for me, music has been a big part of it. I would always want people to sing together when they’re little people because it’s so beautiful and it imprints the joy of music.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.