Launched in London in 1844 and in Boston seven years later, the YMCA has the benefits and drawbacks of a long history. With outstanding name recognition, thanks in part to a hit song from the 1970s that never really went away, the organization constantly deals with outdated and overly narrow perceptions of the range of services it offers. In particular, the federated organization, which serves over 4 million kids and teens annually, has become a leader in providing early childhood services.

Heidi Brasher is senior director of Product Line Cohorts, Strategy and Innovation Movement Services of YMCA of the USA (Y-USA), the national resource office of the Y in the United States. She says the 2650 local Ys in the U.S. are the experts at subject matter and service delivery. “The best practices, models and strategies come from them,” she says. Depending on the needs and strengths of the population they serve, the local Ys might adopt skill-based learning, scaffolded learning, whole child supports, social emotional learning or other approaches.

Operating in urban, suburban and rural settings, with annual budgets that range from $500,000 to $200 million or more, they come in a wide variety of flavors. “We like to say, If you’ve seen one Y, you’ve seen one Y,” Brasher quips. “What they have in common is a commitment to serving their communities.”

Another thing all the Ys have in common is they way they rose to the challenge of the global pandemic. “In March 2020,” Brasher recalls, “they all shut down, and the next day they were providing emergency child care to essential workers, and emergency food to families in need.”

Through Brasher, I got to know three different YMCAs and discovered how they’re amplifying the strengths of families with young children.

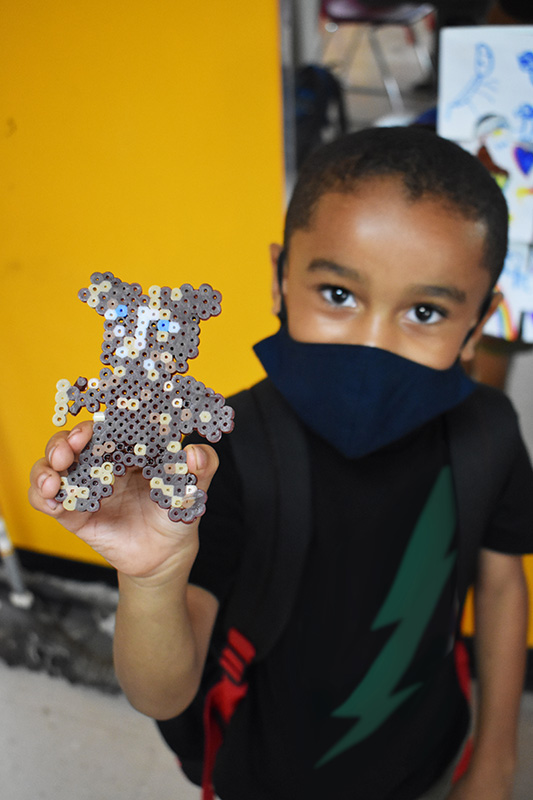

» YMCA of the Triangle, Raleigh. “Our mission says ‘for all,’” notes Mariela Dunston-Torres, senior director of Community Supported Programs. (The mission statement reads: “To put Christian principles into practice through programs that build healthy spirit, mind and body for all.”) Her Y provides nutritional support through repurposed school buses, as well as academic programs like virtual kindergarten readiness programs and a subsidized summer kindergarten readiness program as part of Camp High Hopes.

Dunston-Torres mentions an entrepreneur mother of eight children, six of whom attended Camp Hope, who couldn’t run her business without the Y. “The kiddos learn to stand in line. They learn to raise their hand. They learn to recognize letters, numbers and shapes. Now, when they start school, the teachers won’t think they don’t know how to learn.” A former elementary school teacher, Dunston-Torres notes that her part of North Carolina includes a mixture of African American, Latinx, refugee and Caucasian people. “They might be food insecure. They might be undocumented. They’re good at hiding. Many don’t trust the government, but they trust us,” she says, noting this trust partly stems from the progress the organization has made on prioritizing racial equity.

» YMCA of Greater Cincinnati. Trish Kitchell took a camp counselor job at the YMCA 31 years ago, and she has stayed with the organization ever since, so more than most people she has experienced the out-of-date ideas people have about the Y as a “gym and swim” site. Today she is vice president of Youth Development. “When Covid hit,” she says, “people really saw how we can serve. We showed up for the community. We escalated our services.”

Collaboration increased with public libraries and other community partners. “We dropped the walls and came together,” she says. “And now everyone is looking around at what we accomplished, and we’re saying, ‘Let’s not rebuild those walls.’” She is proudest of how they connect to hard-to-reach families, citing virtual preschool and the supports they provide caregivers in informal settings.

Philanthropic support from local corporations made this initiative possible. While she acknowledges the ongoing challenges of a decimated child care workforce, she is optimistic about partnerships with local colleges to recruit and train educators. “We’re rethinking our business model to support the workforce in this new reality,” she says. Brasher, from Y-USA, says there is renewed commitment to honoring the profession through pay and credentialing. They are also actively investigating how to bring retirees and other nontraditional workers into the field.

» Valley of the Sun YMCA, Phoenix. Jenna Cooper, associate vice president of Youth Development & Community Relations, says the population they serve is 60% people of color and growing more diverse all the time. The mother of a one-year-old boy, she takes advantage of her Y’s benefit of free child care for all full-time staff. This local was poised to open five new child care centers last year, but Covid threw them a curveball.

Now they are back and better than ever. A $25 million gift from MacKenzie Scott to the local United Way has laid the groundwork for a new preschool partnership that will expand services to include one- and two-year olds. Each site will have an early learning director and lead teachers for each classroom. They are also creating more professional early learning positions. The United Way’s Dr. Melissa Boydston points to MC2026, a five-year plan for “Mighty Change in Maricopa County,” as how the community recovers and rebuilds. Third grade reading is a priority of the plan, and, she says, “The YMCA has been a shining example of how we achieve those goals.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.