GoPro cameras are all the rage with skateboarders and other extreme athletes who want to capture their exploits for YouTube. The devices aren’t as well known as accessories for early childhood education research, but they proved to be a perfect fit for an innovative experiment in Columbus, Ohio.

Early Learning Ohio is one of five $4.5-million statewide initiatives funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, a division of the U.S. Department of Education. Dr. Laura Justice, executive director of the Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy at the Ohio State University (OSU), and her team strapped video cameras onto the heads of preschool students so they could monitor the experience of each individual child in the classroom.

“The early education field is making progress,” Dr. Justice says. “There is strong consensus around certain practices, with statistically significant data to back it up.” For example, it’s widely recognized that the classroom is the second most important environment for children, after the home.

At the same time, Dr. Justice says, “We still don’t know how to measure quality in the preschool setting.” Is quality a classroom-level phenomenon? Or does it vary from student to student?

Mathematically, she says, it’s simple to aggregate data and get a classroom score, but a great deal of valuable information gets lost in the process. There’s a tendency to overcount the students with close relationships to the teacher, who congregate at the front of the class, at the expense of the ones whose attention wanders. Those strap-on GoPro cameras are one way of measuring at the child level.

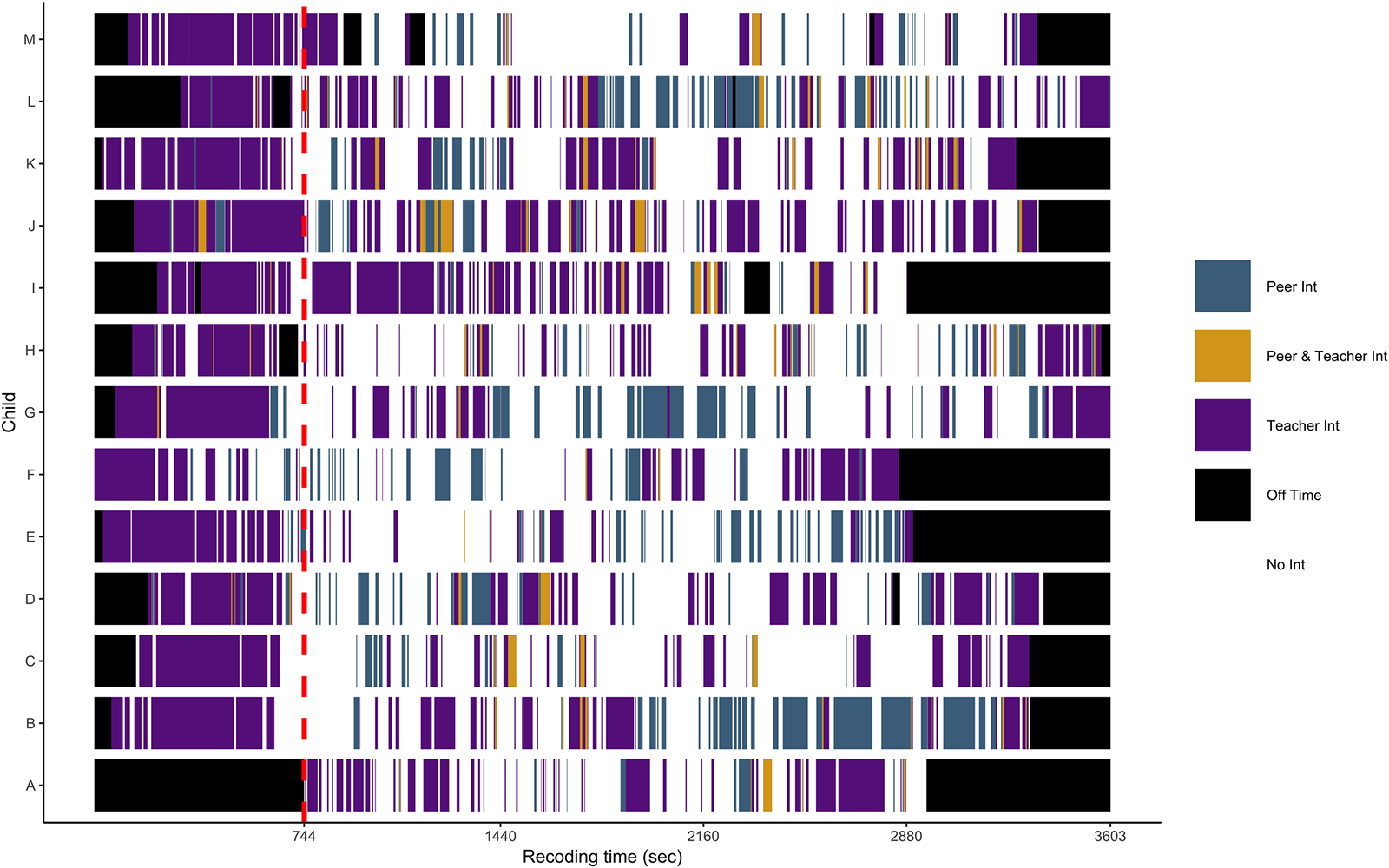

Student experiences tended to be uniform at the start of class, but, as this graphic visualizes, center time (when students move from station to station; after the dotted line) prompted a great deal of variety in children’s interactions. Child “I,” for example, has lots of interactions with the teacher (purple), while “M” has hardly any (white) and “L” has the most peer interaction (green).

Chaparro-Moreno says that the findings may support teachers’ understanding of the “linguistic ecology” of the classroom. Activities that facilitate exchanges with one type of student might not work with another, or not every child in the classroom is exposed to the same activity in the same way. As mixed-age classrooms increase (read more about this accelerating trend), teachers will need to stay on top of varied responses to instruction and adjust it according to the children’s needs.

Some broader context for this study, and the urgency of early-child-education research: The nationwide opioid crisis has hit the State of Ohio with particular force. “Our communities have been hammered,” Dr. Justice says, noting that neonatal abstinence syndrome—the withdrawal condition caused by prenatal exposure to opioids—is widespread. (Read more on this issue.) She adds that she’s heard from educators in the community that they’ve never had parents as disengaged as they are right now. It is increasingly common for grandparents to step into the role of primary caregiver. Poverty, of course, compounds the problem. Half the children in one of their current studies reside in households earning less than $20,000 per year.

“It’s a whole new era,” Justice says. “Communities need to figure out what they’re going to do.” She’s not wrong. Efforts like Early Learning Ohio, and the committed researchers behind them, are undoubtedly part of the solution.

How do you know you can believe a scientist? One factor that should increase trust is when she admits she’s wrong. As Brian Resnick writes in a recent Vox essay called “Intellectual Humility: The Importance of Knowing You Might Be Wrong,” “It’s about entertaining the possibility that you may be wrong and being open to learning from the experience of others. Intellectual humility is about being actively curious about your blind spots.” Dr. Justice recognizes her blind spots when it comes to how preschool children behave and learn in the classroom. She freely admits she was wrong when she thought that most classroom interactions that children have are peer-to-peer. At least for 60 minutes in one classroom of 20 in Columbus, Ohio, the majority of children’s interactions took place with their teachers.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.