For decades, the Educational Alliance on Manhattan’s Lower East Side ran two parallel but separate early childhood programs. If you were a family living in nearby public housing, chances are you attended the Head Start program for low-income families. And if you lived in the neighborhood’s middle-income housing co-ops or signed a lease in one of the glassy new high rises, you could pay tuition for your child to attend the center’s private Reggio Emilia-inspired preschool. When Jacqueline Marks, senior director of early childhood, first started working at Educational Alliance’s Early Childhood at Manny Cantor Center, she remembers “seeing these schools that live side by side in the same building, and thinking, huh, that’s strange.” Parents thought so too, she says.

But in truth, separating toddlers and preschoolers based on family income is the default in early education. It just usually happens in separate programs rather than the same building, making it harder to see. Early childhood programs are likely the most racially and ethnically segregated educational spaces in the country, according to a 2019 data analysis from Urban Institute. Government funding for child care has historically been reserved for the very poor, leading to subsidized means-tested programs for low-income families, with everyone else’s child care options defined by what they can and cannot afford. This has created our current patchwork of early education programs that are rigidly segregated by income and race.

But as Marks and her colleagues sensed, defaulting to segregation is a missed opportunity. It normalizes the experience of segregated schools for new parents, and a growing body of work suggests that racially and economically diverse preschools have significant learning benefits, which some researchers say is not surprising given how much growth in preschool happens through playing and sharing with peers. “Children of all backgrounds learn more on average in racially and socioeconomically diverse preschool classrooms, and diverse early learning settings can help reduce prejudice among young children,” wrote Halley Potter, senior fellow at The Century Foundation, in a recent report that dives into that research and offers ideas for how the federal government can foster integration in universal preschool.

In 2018, Marks and her colleagues began the process of combining the two early education programs which served more than 200 children into one intentionally integrated school. Early Learning Nation talked with Marks about that process and what other programs can learn from their work. She notes that if the Build Back Better plan passes, the growth of affordable and free early education programs could pave the path for more intentional integration.

The interview has been condensed and reorganized for clarity.

KENDRA HURLEY: Educational Alliance’s preschool program has been around since the 1800’s and your Head Start program since the 1960’s. What sparked the decision to combine them?

JACQUELINE MARKS: When I was hired in 2014, there was a new CEO, Alan van Capelle, and Joanna Samuels was the new executive director for the organization’s just-opened Manny Cantor Center. The community center housed the early childhood programs, and our vision was to make it a place where everyone in the community is welcome. But that doesn’t go with having two separate schools. You’d walk into the building and push the elevator button to go to a different floor, and then you were going to a different school with a different funding stream, and a different philosophy. So the three of us who were new all had the same wondering: Why are families separated in the first place? Can we change that?

I soon began to also hear from families that having two schools didn’t seem to be consistent with the mission of the organization. At that point it became really clear we needed to find a way to make our school open and accessible to all.

HURLEY: Why were the schools kept separate for so long?

MARKS: The backend finances are very complex. We’re a direct federal Head Start grantee. We’re also a direct grantee from the New York City Department of Education. And we have many philanthropic gifts. Each of those funding streams has very specific requirements that are different from one another.

For example, in the Head Start landscape you need to do developmental screenings of children and there’s a lot of other reporting that needs to happen. And then the Department of Education has their own system for many of the same things, but it’s in a completely different system, and those systems don’t talk to each other.

To blend the programs is a lot of work and takes a lot of resources, so I think what we had done as an organization, and what we have done as a city, actually, is separate children based on how they’re paid for.

HURLEY: How did your funders react to the idea of blending the two schools?

MARKS: There was a lot of lore out there saying it’s not possible. Our funders had questions like, “Why would you want to do that? It’ll make the finances really complicated.”

But we heard that as an opening. We thought, “Great, if we’re able to figure out the finances, this is something that’s possible.”

After that, one of the things we looked for was: Where’s the model for this? Who are the people that we can talk to and learn from? That’s when we kept encountering places that weren’t able to do it. One economically integrated school we found charged tuition based on a sliding scale, but they don’t receive federal and city funds so did not face the same challenges as us.

In the end, we needed to make sure that the money that comes in is spent as intended, while continuing to hold our progressive pedagogy. That required a pretty complex finance team. We are a large organization and were able to make that happen, and at this point, all of our funders are very interested in the work we’re doing. They’re now connecting us to other schools and programs that are interested in doing this. If the Build Back Better plan passes, I think more schools will have an easier time with the funding piece.

HURLEY: How did you decide programming for the blended school?

MARKS: We wanted to combine the best of what we had. Our tuition-based school is progressive and inspired by the schools of Reggio Emilia in Italy. Our curriculum is co-constructed with the children and teachers and families through observing what the children are interested in and creating opportunities that are specific and relevant to them. It’s based on the idea that all children come to school capable and full of potential, and that every family has much to contribute. We wanted to give everyone access to that.

Our Head Start program, while more traditional in nature, had thoughtful social work supports that we thought all families could benefit from.

To combine them, we were again unpacking the lore around what was possible with our funders. We learned that you actually can have what’s called an “emergent curriculum” like ours through Head Start. On their grant application, you select from a box of options for what curriculum you’re using, and we just had to check “Other,” which means we would need to prove that our curriculum is a research-based effective curriculum, and the emergent curriculum we use is exactly that. Once we knew we could do that, we knew that what we were hoping for was possible.

HURLEY: How did staff and families adjust?

MARKS: Many families come to this neighborhood because they want to raise a family in this beautiful, diverse landscape. So for families it felt right, like this is something that has needed to happen for a long time. Our Policy Council, which is the Head Start term for Parents Association, has been working to create ways for families to come together outside of the classroom too, though due to the pandemic these gatherings have been a bit different and smaller than planned.

With teachers it has been more complex because that’s where we’re asking people to make change. When you have two schools with two philosophies, and both groups of teachers are deeply rooted in their own understanding of early childhood education, it can be challenging to ask for change. If you’re used to taking a curriculum book off the shelf and following it, that can be hard, because that’s no longer the school’s philosophy.

So we gave ourselves lots of time to come together. We started professional development with teachers before we combined the schools as a way for teachers to begin to get to know each other and learn about the strengths of each program. We learned that one teacher may have a really strong background in progressive education, while someone else may have a strong background in building trust with families. For teaching teams we thought about who’s going to work well together and complement each other.

HURLEY: What advice would you give other programs interested in creating economic integration?

MARKS: When programs have different funding sources that serve different populations separately, children then grow up through those different streams. They go to public school according to who they’re in preschool with, and it continues from there and you have these segregated schools. As preschool providers, we can help stop that cycle.

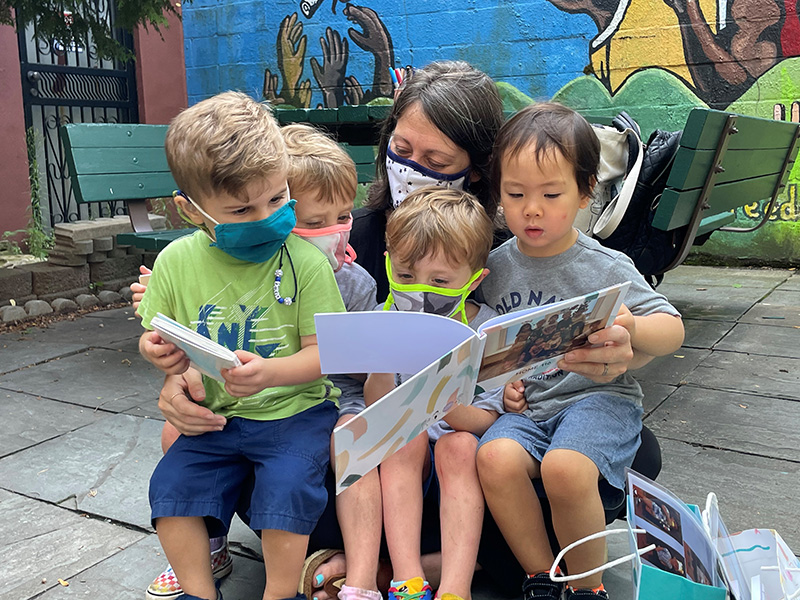

Now, every day during morning drop-off, I see the relationships that families from all backgrounds are building as they help each other fold a stroller, or sit together on a bench and talk about their weekend. It’s happening because they have the opportunity to be together.

We need more of this, and I think that some of the federal funding that will hopefully soon roll out for child care and pre-K can create more opportunities for economic integration. My advice to programs in diverse neighborhoods is to absolutely do this. This is important.

Kendra Hurley

Kendra Hurley is a journalist and researcher focused on cities, families, policy and economic issues. Her journalism has appeared in The Atlantic, Bloomberg's CityLab, Slate and other publications. She was previously a policy researcher and editor at The New School, and also spent several years as a mentor-editor for a magazine written by and for teens in foster care.