States are taking early childhood education seriously. A recent report from the Alliance for Early Success documents the progress. (See our story on the related Hunt Institute webinar.) But are they doing enough?

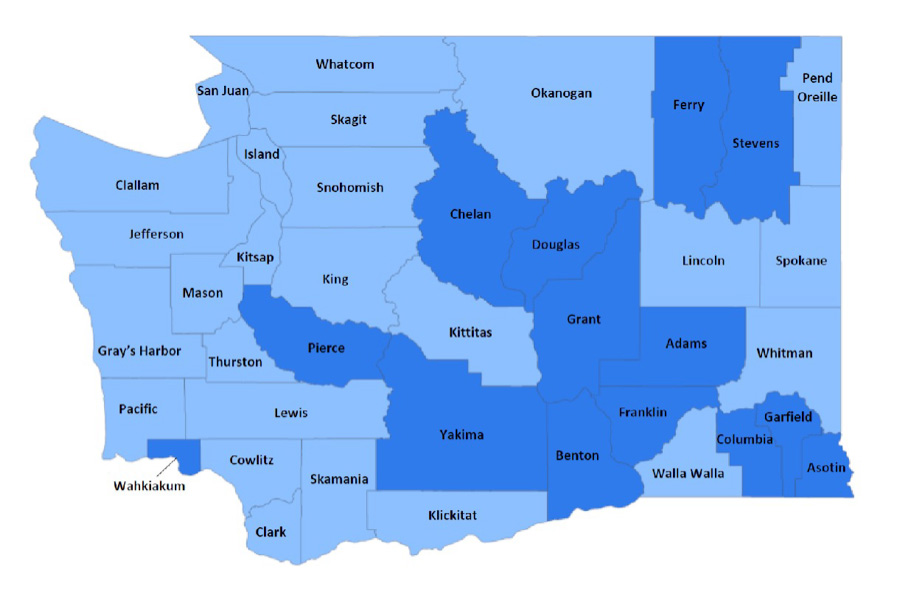

Take Washington State, for example. The 2021 $500 million Fair Start for Kids Act augments the state’s child care and early education programs and expands access to support services. It also shores up the business of child care through health insurance, professional development and scholarships. Nevertheless, according to a recent publication, “these investments fall far short of ensuring universal access to preschool.”

“Preschool for All: A Strong Start for Washington State’s Children” articulates an ambitious vision to bring the Evergreen State up to speed. It proposes two investment options—$795 million for the “Free and Sliding Scale Option” and $1.53 billion for “Free for All Option”—either of which could be implemented over a 10-year timeframe.

Earlier this year, the Russell Sage Foundation published a second edition of Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality. The update refreshes arguments made in the 2016 edition for such evidence-based policies as… read more

I spoke to two of the publication’s authors—Dr. Christina Weiland, associate professor, School of Education, University of Michigan; and Tim Burgess (lead architect of the Seattle Preschool Program approved by Seattle voters in 2014 and expanded in 2018) —about the recommendations and the potential for bringing them about. They maintain that this is a critical moment for decisive action, regardless of what happens at the federal level with the Build Back Better Act.

“Washington State has its own budgetary and political realities,” says Burgess, “but most of what we propose could lead to universal preschool in most states.”

Five core principles underlie the Preschool for All vision:

1. Parents know best. Some parents want to stay home with their babies if possible. Some prefer entrusting the care of their young children to a family member or neighbor; others are more comfortable sending them to a center. Mixed delivery makes early education a more complex challenge than K-12 education, but as a group, Burgess says, “Parents really do believe starting early is important.”

According to a 2020 survey, nearly 9 in 10 U.S. parents support optional public pre-K for three- and four-year-olds. Evidence points to the value of early childhood education (ECE) for a variety of life outcomes, and parents see the impact with their own eyes. It also helps that accessible, reliable programs mean that working parents can focus on their jobs.

The Preschool for All plan, says Carla Bryant, executive director, Center for District Innovation and Leadership in Early Education, “honors parent choice by acknowledging the importance of a mixed delivery system while anchoring the system in a high-quality preschool program.”

2. States have the power. Weiland and Burgess explain that if states could do comprehensive, high-quality prenatal-to-five care alone, at least some would have already done so. The federal dollars and framework of Build Back Better stand to make a huge difference. However, states are ultimately in the driver’s seat. State policymakers will make decisions about how that money is spent. (Sometimes, municipal governments take up the charge.)

Elected leaders in conservative, liberal and mixed states alike are pushing for new ECE solutions and are learning from one another. Burgess points out that Republican-led states, including Oklahoma, Georgia and West Virginia, have passed universal pre-K measures in the not-to-distant past. “This remains a bipartisan issue,” he asserts.

👉 Read the Hunt Institute’s summary of ECE provisions in Build Back Better

3. Early education is a proven antidote to inequality. What Casey Osborn-Hinman, a former kindergarten teacher in Washington, likes most about the plan is that it “would increase economic security for parents and providers alike.”

High-quality early learning experiences also better prepare children for kindergarten and can result in long-run impacts on outcomes like health, education and earnings (see, for example this summary of the legacy of the longitudinal Abecedarian Project in North Carolina).

In an instant-gratification political environment, Professor Weiland observes, investments with benefits that take time to materialize can be difficult to explain and justify. “Nevertheless,” she maintains, “if we truly want to address inequality in all its forms—education, health and economic—the first years are critical.”

👉 Read more: “New ECE Research Looks Back and Ahead”

4. We can provide access and achieve high quality at the same time. Access without quality isn’t what families want and can even harm child development. Quality without access leaves too many families out of the picture, which allows inequities to persist and deepen. Weiland and Burgess believe we can achieve both, given sufficient funding and a willingness to collaborate within states (and within communities, through partnerships between public schools and community-based providers).

When should we start? As soon as possible. Where should we start? Communities with more families living in poverty, say Weiland and Burgess, who also note that learning sites throughout the country could stand to update their curricula to reflect current research into the ways young minds learn best. (Read Dr. Weiland’s recent paper on evidence-based curricula and the supports needed to implement them.)

5. A comprehensive approach won’t pit babies against preschoolers. Too often, in policy conversations, due to a scarcity mindset, funding for infant and toddler early care and education is pitted against funding for preschoolers. As with the supposed dichotomy between access and quality, a strategic and integrated ECE system doesn’t have to be an either-or proposition. In reality, says Burgess, “Relatively less expensive preschool education is critical for subsidizing the more intensive care of the youngest learners. They go hand-in-hand.” Weiland, Burgess and their co-authors envision an intentional, fully integrated early learning system in Washington and other states, including all the essential prenatal-to-five services.

Recently retired state representative Ruth Kagi views the Preschool for All plan as an important next step. “Washington has done an excellent job creating and supporting a high-quality preschool model,” she says, “but it serves only our lowest income children and ranks 36th in the country in terms of access. Funding universal pre-K is an investment in our K-12 education system’s success, and in our current and future workforce.”

“There simply aren’t enough resources today dedicated to early learning,” summarizes Professor Weiland. “Money matters, but it also matters greatly how we invest that money. Doing this right will take all of us.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.