This magazine uses the word crisis a lot. We’ve reported again and again that early childhood education in America is at a breaking point. Inadequate wages, deepening mental health trauma (for families, children and educators alike) and a welter of other obstacles stretch out ahead of us into a troubling future. It’s no wonder that a new generation of child care activists has decided that playing nice doesn’t work any more.

As executive director of the Alabama Institute for Social Justice (AISJ), Lenice Emanuel sees her job as “selling freedom.” She’s more than willing to use protest, confrontation and the tools of a community organizer in the fight for freedom and justice. “Nothing of importance was ever changed in this country without upsetting the status quo,” she says.

AISJ originated in 1972 as the Federation of Child Care Centers of Alabama (FOCAL). With the name change, which occurred in 2017, Emanuel says, “We have become an advocacy organization focused on empowering women and minorities, but children remain our first love and our foundation.” It doesn’t make sense to focus on child care without addressing racial and gender equity or recognizing the interconnected historical, economic and political issues robbing children of their potential.

The State of Alabama presents more entrenched challenges than most other parts of the country. Emanuel points to the December 2017 findings by Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights (see sidebar), which compared living conditions in rural Alabama to those in the developing world. Although the state’s early education initiatives have been celebrated in Early Learning Nation and in a well-regarded documentary, she maintains, “Alabama is really not trying to make investments to dismantle poverty or to enfranchise marginalized people.”

She continues, “There is a culture here of, ‘We’d much rather look good than actually be good.’ It’s a Southern thing, right?”

Emanuel comes by activism naturally. Her parents attended Alabama State University during the Civil Rights movement and marched with Dr. King, and today her father pastors a church in the City of Prichard, in Mobile County, across from the former site of the Harlem Duke Social Club, where B.B. King, Ray Charles, Etta James and more performed. Growing up, Emanuel remembers, her parents took in homeless people and mothers running from domestic violence.

After graduating from Spring Hill College, Emanuel went to work for the Mobile YWCA, where she received her foundational training in racial and gender equity. Her work with AISJ, however, pushed her into next-level community engagement, where systems change centered her work and she began engaging in what she calls “hardcore, grassroots organizing, in the trenches, working with some of the poorest and most marginalized people in the state of Alabama.”

Along the way, she has learned to navigate rural poverty as someone from a marginalized community, but whose upbringing was more middle class, as her parents placed a premium on education, ensuring her competitive academic exposure. To that end, she acknowledges that, “There have been times I’ve had to check my own class at the door, to really understand what the true values of parents were, when observing the confidence some had in leaving their children in centers that, at times, operated in less than ideal conditions.”

“Demonization of the poor can take many forms. It has been internalized by many poor people who proudly resist applying for benefits to which they are entitled and struggle valiantly to survive against the odds. Racism is a constant dimension and I regret that in a report that seeks to cover so much ground there is not room to delve much more deeply into the phenomenon…”

[Read more]“They want their children to be safe,” she says. “They care nothing about these rubrics that we want to invest so much money into.” She contends, “Quality is subjective, and for many Black and often poor families, quality is quantified in the personal character of those caring for their children.”

Given the opportunity to join AISJ in 2015, Emanuel jumped at the chance to follow in the footsteps of one of her idols, MacArthur fellow Sophia Bracy Harris, who had integrated the previously all-white Wetumpka High School and gone on to found FOCAL with a group of activist women. “How do you stay in the game this long in a state like Alabama?” Emanuel marvels. In her first hundred days as executive director, she set out to meet a hundred people, including 80 child care providers. The conversations she’s had before and during the pandemic inform her approach and fuel her commitment to speak her truth. “I’m just not the kind of person that’s going to tell you that something is that is not,” she says.

In Emanuel’s view, the state’s leaders—including some praised by Early Learning Nation—“are in deep need of cultural competency. They’re so myopically focused on pushing their agenda through that they don’t listen to the people in the field.”

“It is morally wrong,” she asserts, “to just continue to exacerbate the conditions of people when you are in a position to make a difference. It is morally wrong to have American Rescue Plan money that was designed to help people in this pandemic used to build more jails.”

Invited to take part in budget conversations with the leaders she’s criticized so relentlessly, Emanuel almost declined, but ultimately decided to use her voice. “I’m going to stay at the table,” she says, “but at the same time, I’m going to continue to challenge them.”

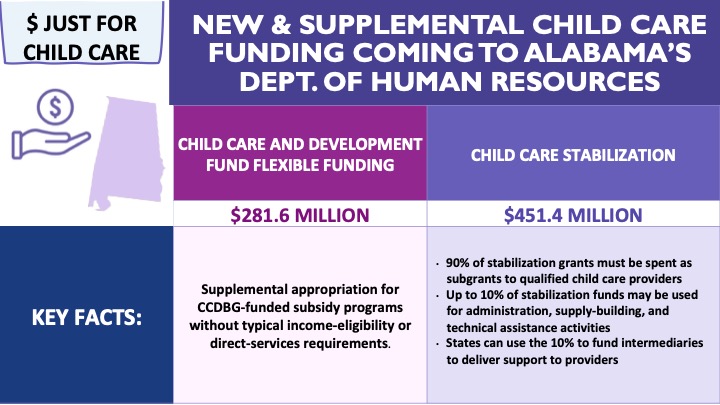

AISJ collaborated with Elizabeth Gaines and the Children’s Funding Project to demonstrate how federal funding could make a much bigger difference for Alabama families.

👉 Experience the Children’s Funding Project’s Database

“Everyone knows Lenice is a fighter,” says Gaines, “but it’s the way she uses data to tell the story of Alabama child care that makes her so effective.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.