“Literacy learning for young children is not bound in time and space,” proclaims Susan Neuman’s latest paper for Reading Research Quarterly. “Early Literacy in Everyday Settings: Creating an Opportunity to Learn for Low- income Young Children,” coauthored with Jillian Knapczyk, celebrates the potential for “intentionally designed everyday spaces” such as laundromats, grocery stores and banks to ignite a love of reading. I spoke to Neuman, professor of childhood and literacy education at New York University, about her findings, inspirations and convictions.

Your name has become strongly associated with the concept of book deserts and the vast difference between a home that has books everywhere and a home that doesn’t. How did you come to look at that variable?

It was literally out of frustration. I was in Philadelphia at the time, and we were trying to understand why so many communities seemed to be succeeding and others not. We conducted an audit that turned up enormous differences in access to print for those children who were living in concentrated poverty. It was not just in the home. It was in the child care institutions, it was in the library, in the school library. It was everywhere.

It was literally out of frustration. I was in Philadelphia at the time, and we were trying to understand why so many communities seemed to be succeeding and others not. We conducted an audit that turned up enormous differences in access to print for those children who were living in concentrated poverty. It was not just in the home. It was in the child care institutions, it was in the library, in the school library. It was everywhere.

How did JetBlue get involved?

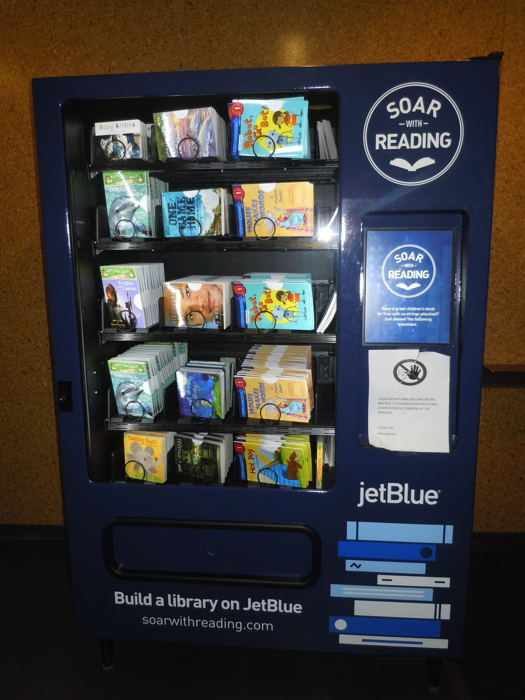

They have a social responsibility office, and they have been giving books for a long time. They wanted to gain a better understanding of the impact they were having. So we selected [D.C. neighborhood] Anacostia as well as Detroit and Vermont Square in Los Angeles. And again, we saw massive differences. We saw that those places with concentrated poverty virtually had no books. The sheer inequity was extraordinary to me. And it seems like an easy fix, but somehow it hasn’t been fixed.

👉 Discover JetBlue’s Soar with Reading program

By itself, our small win might seem…small. However, small wins can lead to short-stacked gains to create a big win.

More books in the hands of kids=more literacy experiences and opportunities for kids.

Read more 👉 https://t.co/1gizS5jg3Q

and visit https://t.co/oABobsPdE2 pic.twitter.com/VxnGtX6yAA— Susan Neuman (@SusanBneuman) August 26, 2022

What do we know about the best ways to get books out there?

First of all, choice is critical. Book reading is not just about reading. It’s about finding out stuff and becoming an expert in a domain. So kids want to be smart, or they want to be funny or they want to have the best knock-knock jokes. Another thing is to make it precious. JetBlue’s vending machines dispense books wrapped in cellophane. The children say, “Oh my gosh, this is mine. It’s never been touched.”

Are you tracking what’s popular? Is there a surprise runaway bestseller?

The ones with diverse characters. In Anacostia, which is primarily African American, all those African American books were taken. TV- and movie-related books, too, which is fine, we’re trying to establish that early reading habit very early.

👉Read more: Checklist aims to help teachers create reading oases in book deserts

How do create a culture of reading?

We’ve tried very hard to find the trusted leaders in a community, and every community will be different. In Anacostia, it was Pastor Maurice, who always had a gaggle of kids hanging out with him and who believed that kids should be reading. He was a big prophet of reading.

👉 Read more: Meeting (and Teaching) Families in Unexpected Places Can Transform Cities

We’re always looking for the big bang. What is the big thing that’s going to make the difference? But I’m convinced it’s not going to be just one big thing. It’s going to be collaboration among community members working together to support our children, to view every single child in that neighborhood as our children, and coming together in all sorts of different ways to support literacy early on.

What worries you most about the way reading is taught?

We still have this pedagogy of poverty that the children who live in poverty should acquire nothing but basic skills and basic foundations. People are returning to the importance of phonics and phonemic awareness and forgetting that these children have interest, choice and a love of reading when we give them opportunity. It really worries me that we haven’t learned the lessons of the past.

At the end of the 8-week project, over 22,000 books were distributed through these bright blue vending machines.

What was the community feedback?

“This is so needed.”

“This is the greatest thing ever!”

“This is what the community needs!”. #LiteracyEquity #EndBookDeserts pic.twitter.com/OP9kw7Nuh4— Susan Neuman (@SusanBneuman) August 25, 2022

What gives you hope for the future of literacy?

I’ve spent a lot of time working with children in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. We have a vocabulary intervention for 3- and 4-year-old kids, and they are so capable and such robust language learners. We just had this wonderful study where the children learn the word ‘hypothesis’ and it was just by watching videos.

I noticed a lot of references in this paper to Urie Bronfenbrenner’s 1979 book The Ecology of Human Development. How did this work shape your approach?

Bronfenbrenner really inspired me, and the reason is that is it takes a community in a neighborhood to create a literacy learner. It’s not just parent involvement. And typically what we’ve done is we’ve relied on the school, we’ve relied on the home, but we haven’t recognized that the community or the neighborhood has a powerful influence on children’s learning. Much of my work in the past year in particular has focused on literacy in barbershops and different social offices, in nail salons, laundromats and playgrounds. I’m trying to surround children with the notion that books matter.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.