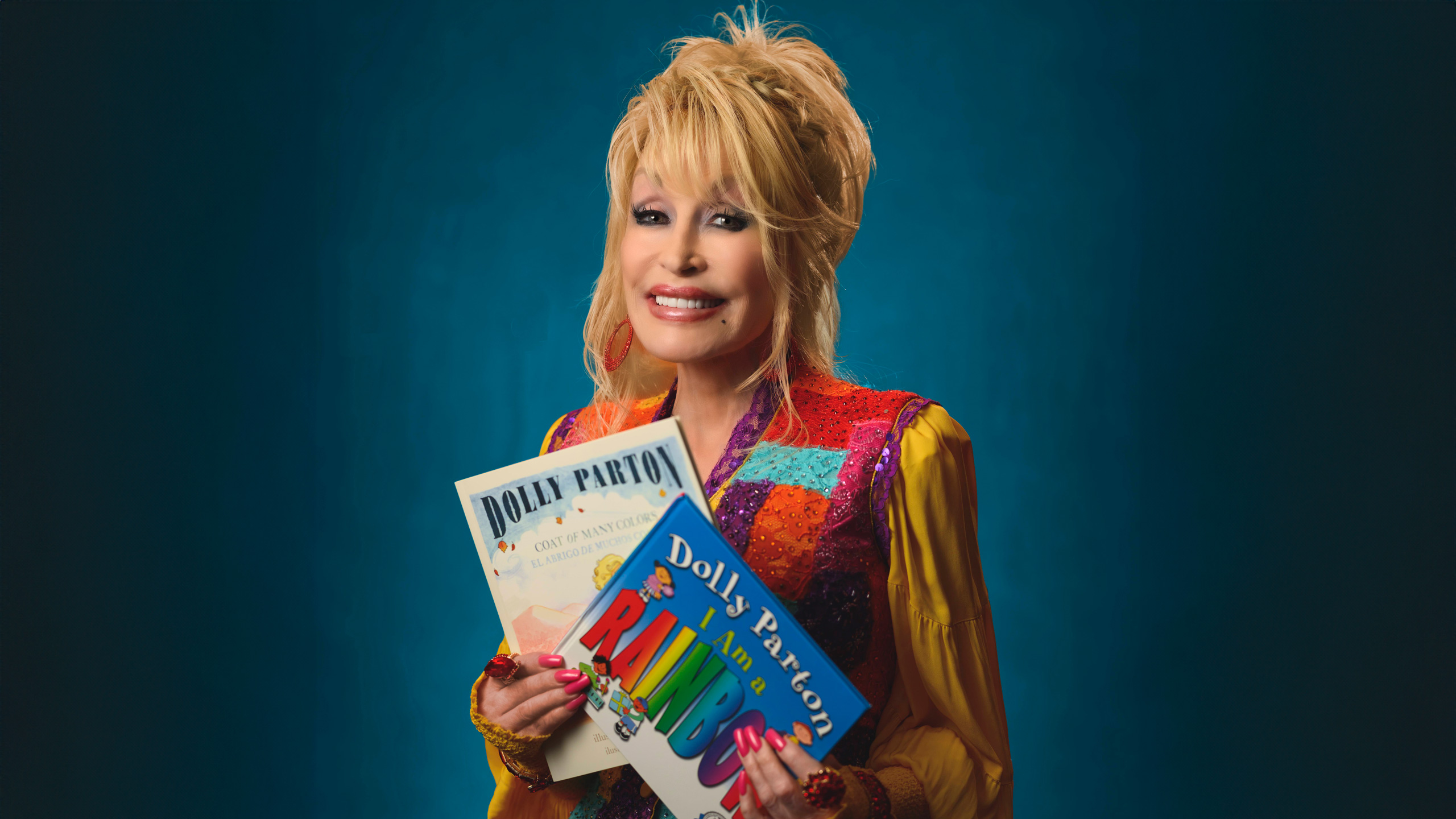

Dolly Parton sticks a lot of books in the mail.

To be clear, the music legend, business executive and philanthropist doesn’t bring 2.4 million children’s books to the post office every month and drop them in the mailbox herself, but she is far more than just the face of Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library. Every chance she gets, Dolly Parton reads bedtime stories on video and shares her inspiration behind the gift-booking program and The Dollywood Foundation. Best of all, as soon as every ZIP code in a state is covered, she shows up in person to celebrate.

Launched in 1995, the Imagination Library sends free books to 1 in 10 U.S. children under 5 years old. The program operates in all 50 states. Here’s a look at how Dolly’s delivering early literacy in three of them.

Arkansas

“The children don’t know her as a famous singer,” laughs Charlotte Rainey Parham, Ed.D., executive director of the Arkansas Imagination Library. “To them, Dolly is the book lady.”

To help pay for the books and distribution, the Arkansas Imagination Library receives funds that originated as the largest federal grant ever received by the Arkansas Department of Education. Thanks to this investment, 43% of all the eligible children in Arkansas are enrolled, says Brooke Ivy Bridges, affiliate resource director of the Arkansas Imagination Library.

“And we’re working hard to increase that number,” Bridges says, describing efforts to develop partnerships with birthing hospitals. “That way, before a family even leaves the hospital with its new baby, the newborn is registered. By the time the child starts kindergarten, he or she will have a home library of 60 books.”

Before coming to work at the Arkansas Imaginary Library, Bridges was involved as president of one of the Rotary clubs in Little Rock—and as a mom. “My daughter loves Dolly,” she says. “She has grown up seeing a life-size Dolly Parton cutout here in my home office. She loved her books from the Imagination Library.”

In many rural communities, Bridges notes, public libraries are less accessible, so home libraries become even more important. She adds that, in multigenerational households, grandparents, aunts, or uncles also get involved in reading to children. “The ultimate goal is to create a family conversation around the love of reading,” she says.

Colorado

Laura Douglas, Imagination Library of Colorado’s director of operations, says there have been Imagination Library programs in communities throughout Colorado for about 15 years. But it really took off in November 2021 when Governor Jared Polis signed legislation to make it part of the state budget. “Half of our book bill is paid by the state of Colorado,” she explains, “and the other half is paid by the local affiliates.”

Douglas, who previously worked for the History Colorado Center, travels across the state, meeting with local affiliates and training them how to implement the program. She and her team are working to improve access where early literacy resources can make the most difference, including Spanish-speaking migrant communities.

Douglas notes that these families especially appreciate dual-language books. Partnering with the state’s Migrant Education Program is vital to the mission but presents challenges. “Those children don’t necessarily have a permanent home location or a permanent address,” she says, “So those books are mailed to a local preschool, rec center or other central location.”

Douglas appreciates the cultural diversity of the books in the program and singles out Emily Kate Moon’s Drop: An Adventure through the Water Cycle as a personal favorite.

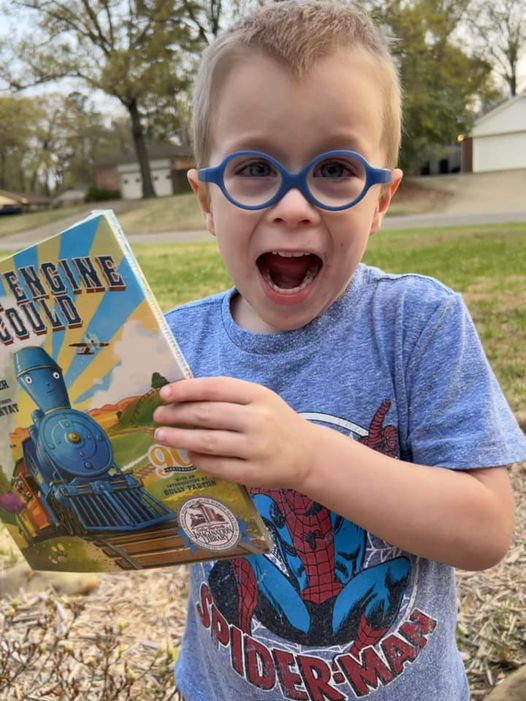

A panel of experts chooses the books for distribution. The U.S. book selection committee currently includes two librarians, an author, a mental health professional, a children’s book buyer for a store and a retired teacher. The first book to arrive is always The Little Engine That Could, and the last is Look Out Kindergarten, Here I Come! In between, Eric Carle’s Hungry Caterpillar series and Anna Dewdney’s Llama Llama books are perennial favorites, along with such favorites as Goodnight Gorilla and The Snowy Day. (See the list.)

Jack Tate, president and CEO of Imagination Library of Colorado, captures the sentiment of many of the state programs when he emphasizes the importance of partnerships to drive expansion. Rotary Clubs, libraries, early childhood councils and United Ways have been especially enthusiastic. “One of our United Way affiliates told me why they liked the program,” he says. “They see it as a tangible way to bring the whole community together, because all the children get books, and that has a really great way of unifying a community.”

California

The California State Library runs Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library in California. State Librarian Greg Lucas credits Governor Gavin Newsom and bipartisan support from Senators Shannon Grove and Toni G. Atkins for a $68.2 million one-time funding commitment in October 2022 to promote early literacy through free books.

A self-described “broken-down old newspaperman,” Lucas is preparing to fill leadership roles to conduct this massive undertaking. “We have 2.4 million kids under five. Los Angeles alone has 500,000,” he says. “That’s not what the program looks like in Delaware. California is the most diverse group of people that have ever been brought together as equals in the history of human civilization.” Chaired by Jackie Wong of First 5 California, the Imagination Library board in California is actively shoring up existing local partnerships.

Lucas says the San Diego Literacy Council is jumping in feet first, prioritizing the ZIP codes with the lowest literacy rate. He also mentions Long Beach, which has the largest population of Cambodian Americans in the country. Other communities speak Mandarin, Vietnamese, Russian and Farsi, among other languages.

Lucas is optimistic that those 2.4 million young children in California will get their books, thanks to the simple power of its model: “A package arrives, addressed to you, with a cool book inside that’s going to make you think and make you eager to get the next one.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.