Claudia Goldin, recent Nobel Prize winner and the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University, is a trailblazer who deeply understands that the forces holding women back at work are both structural, and the result of short-sighted public policies that women disproportionately bear the brunt of. Her talks about the road contraception opened for women seeking higher education are profoundly moving in exploring what generations before us undertook to exist in a male-dominated workforce. Can the lesson of birth control be useful in the fight for child care?

Those of us who write about work, family, and care have long referenced Claudia Goldin’s work and texts in our reporting. Goldin, 77, built her career on understanding and addressing the systemic obstacles women face at work—and only by systematically understanding what holds back women, can we move forward. (Hint: it’s not just gender bias, though Goldin admits our problems might be easier to solve if they were as simple as human perception.)

Her research on women and our evolving relationship with work has proven that policies and workplace structures, not just new ideas, have helped women to succeed and closed the education gap.

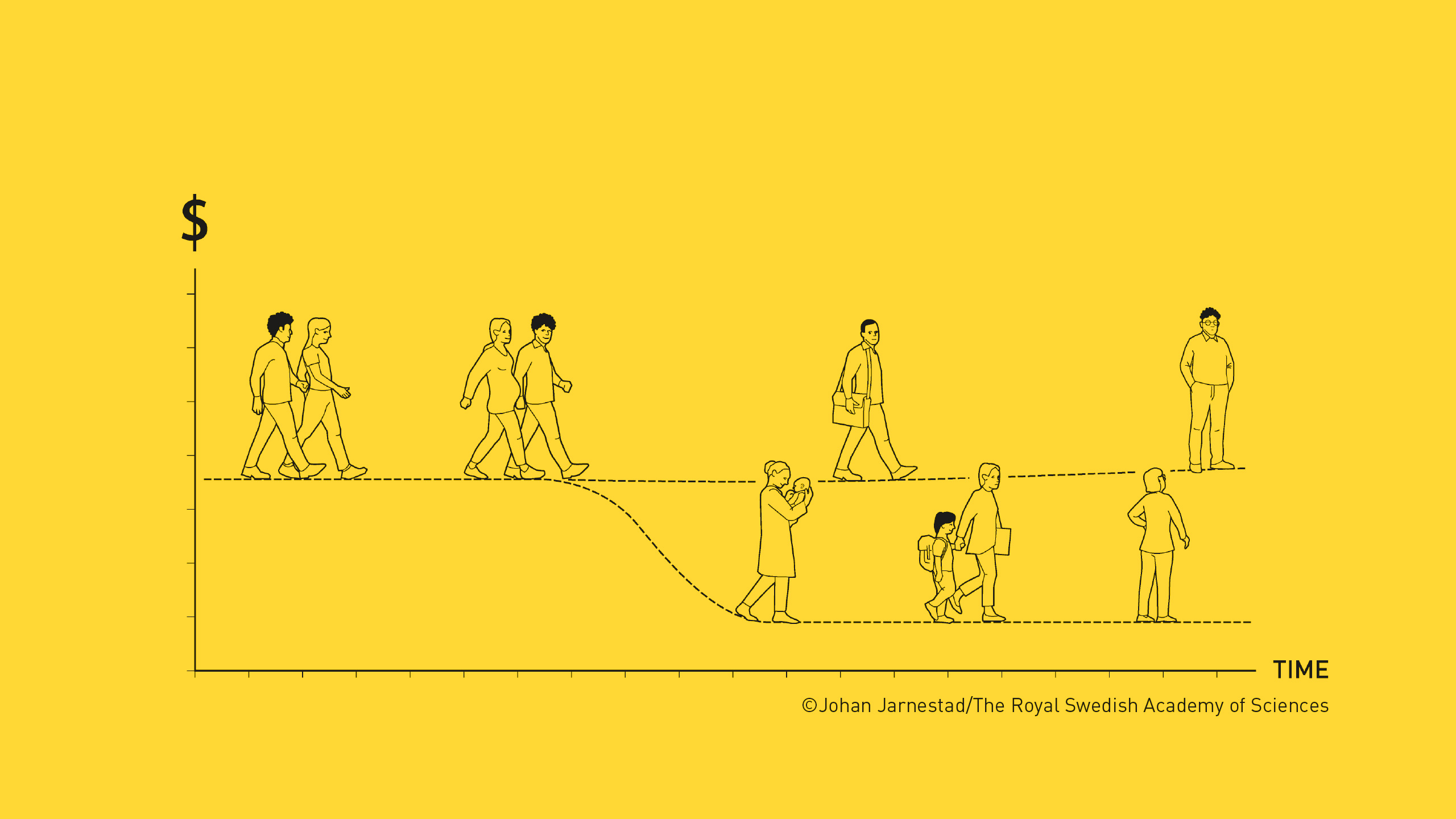

Perhaps most importantly, Goldin’s research shows, women’s desire for flexibility at work, comes at a cost: By eschewing the “greedy jobs,” which demand more hours and less control over one’s schedule, women are stepping away from the positions that pay far more.

And the primary reason driving women away from such on-call, drop-everything-at-a-moment’s-notice work? The caregiving responsibilities they’re shouldering at home.

The pivotal role of caregiving in our economy has become increasingly visible in recent years, spotlighted by a pandemic that showed what many people have been saying all along: we need child care for our economy to function—particularly if we consider the obstacles to women’s participation.

This focus on women and work has the potential to grow further now that Goldin, a professor of Economics at Harvard University, has a new accolade to her name: the first solo woman to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Why Access to Contraception Meant Access to Careers and Education

Birth control existed long before women could easily access it. When the FDA approved the birth control pill in 1960, it was for married women only. Goldin talks about her own life during that period as a college student at Cornell University, where women would put fake rings on their fingers and convince medical providers that they were married in order to get a birth control prescription.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s, when state laws changed, that younger, unmarried women had the same access to contraceptives. No longer did women need a fake ring or marital alias to have the same reproductive rights as their married counterparts.

But even with higher education, prominent careers and heady ambition, the gender wage gap persisted, and Goldin wanted to know why. She identified three primary causes to the earning chasm: the motherhood penalty, the price of being female and the fatherhood premium. (Taken together, this is called the “parental gender gap.”)

A major shift was taking place. By giving a woman wide access to birth control, she could have more autonomy in her life choices. She could stay in school longer and pursue a graduate degree, marry later after her education was completed or her career already started, and she could plan her family accordingly, choosing when to have kids and how many.

Goldin’s research, which she conducted along with her husband, Harvard economist Lawrence Katz, found that by 1970, there were substantial changes in women’s long-term professional education attainment and the age in which they married, thanks to contraception.

But even with higher education, prominent careers and heady ambition, the gender wage gap persisted, and Goldin wanted to know why. She identified three primary causes to the earning chasm: the motherhood penalty, the price of being female and the fatherhood premium. (Taken together, this is called the “parental gender gap.”)

As children grew up—or, more bluntly, as child care needs decreased—and women were able to log more hours at work, the motherhood penalty reduced (though more so for those with less education while the gap stayed wider for people who could stomach the churn of the “greedy jobs”).

Safe, Reliable and Legal Birth Control Changed Lives. Can Child Care be Next?

Goldin’s findings show the stark barriers to women’s work success and how caregiving plays an outsized role. And this is why the next watershed moment for women and work could be the wide availability, in some states, of high-quality child care.

Two states, Vermont and New Mexico, are making historic investments to provide near-universal care from birth to age 5 for the families in their states. The structure of these child care supports differ, but they share a common theme: more families will have more access to quality child care, and they will pay less out of pocket for it. While these programs may take several years to get off the ground, data will start to emerge much sooner.

We are likely to find that access to child care—similar to access to contraceptives—will have an outsize positive impact on women’s access to work opportunities and aid in closing the gender wage gap. Data already exists to support this. The number one reason women leave or change jobs is due to inaccessible and unaffordable child care, and nearly half of mothers who remain unemployed left the workforce due to child care issues.

The United States provides no federal child care infrastructure, including no paid family leave to take care of a new baby, and this disproportionately affects women. The gender quit gap—which looks at the rates of men and women quitting work—is the widest in the states with the most child care disruptions during the pandemic. States with some of the lowest rates of child care disruptions saw no gap in quit rates between men and women.

Studies have found that reliable access to child care can generate an additional $79,000 in lifetime earnings for mothers, and even more for families with high-earning professional jobs. A study conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services found that if child care spending was increased by just ten percent, over half a million women with young children would be newly employed. We also know from initiatives in Quebec that access to universal child care increased the number of women who were able to work, which increased Canada’s GDP.

Curating state-specific data on such programs makes a difference and allows other states to adopt similar initiatives. More than 20 years ago, California created the first paid family leave program, paving the way for data and evidence for other states to find the political wills to create their own. Today, 13 states and the District of Columbia have paid family leave in place.

Our country now faces a pivotal moment with child care. Evidence exists that high quality child care benefits children and families alike, and that improving a woman’s earning potential boosts family incomes as well. We finally have trailblazing states who are just beginning to build out the necessary child care infrastructure, and the same lessons that Goldin applied about birth control and greedy jobs can be extrapolated onto our country’s decision about when and how to invest in care.

The failure of Build Back Better’s proposed investments was a significant blow, but it also showed us what could be possible. Perhaps there is a future Nobel Prize winner who can use such longitudinal data and econometrics to make this case. And maybe then will there be enough evidence to persuade the decision-makers in our country that federal investment in child care is needed, across the board.

Rebecca Gale

Rebecca Gale is a writer with the Better Life Lab at New America where she covers child care. Follow her on Instagram at @rebeccagalewriting, and subscribe to her Substack newsletter, "It Doesn't Have to Be This Hard."