In a 2016 Atlantic feature, Alana Semuels calls Fairfield County, Conn., the epicenter of American inequality. “Bridgeport,” she writes, “an old manufacturing town all but abandoned by industry, and Greenwich, a headquarters to hedge funds and billionaires, may be in the same county, and a few exits apart from each other on I-95, but their residents live in different worlds.”

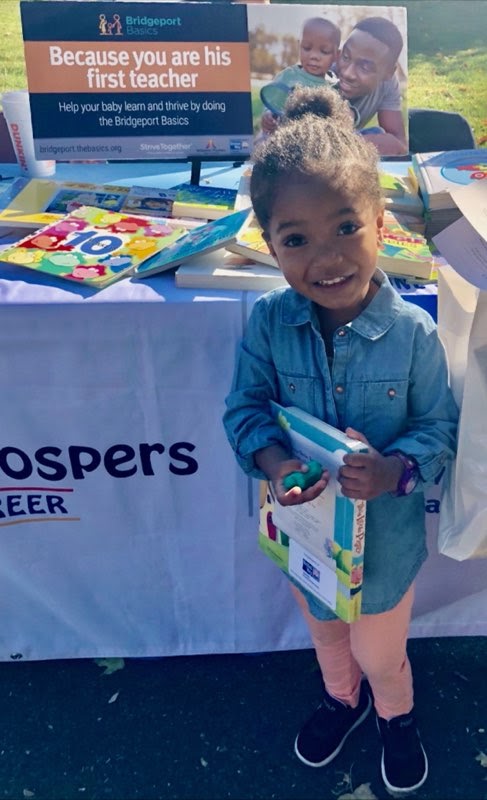

Semuels’s article asks important questions about this grave imbalance, but she overlooks the crucial opportunity—indeed, the obligation—it presents for philanthropy to demonstrate its value. Baby Bundle, an initiative of the United Way of Coastal Fairfield County’s Bridgeport Prospers, represents a sweeping effort to equip young children and their families in Connecticut’s largest city with the supports they need to thrive. Local philanthropists, as well as the Pritzker Children’s Initiative, fund the Baby Bundle. I interviewed Bridgeport Prospers’ Allison Logan and Janice Gruendel and they introduced me to two people taking part in the systems change it is bringing about.

👉 Podcast: The New Neighborhood’s Joan Lombardi explores the Baby Bundle http://bit.ly/New-Neighborhood-episode4

The United Way Team

Dr. Gruendel, a senior consultant with Bridgeport Prospers and a fellow with the Edward Zigler Center in Child Development & Social Policy at Yale University, notes that a single statistic “made the community shudder” and gave rise to the Baby Bundle: three-quarters of the city’s three-year-olds were not hitting their developmental markers. It didn’t take a Ph.D. to understand the long-term ramifications of letting this predicament fester year after year. In the absence of targeted intervention, toddlers who don’t meet their developmental milestones become kindergarteners who aren’t ready to read, with dire outlooks for later metrics such as high school graduation and avoiding incarceration. Behind the statistic about three-year-olds, Dr. Gruendel said, was “a community in deep pain.”

“We knew we weren’t going to program our way out of this,” recalls Logan, the executive director of Bridgeport Prospers. As she explained, in the past, when a crisis reared its head, the tendency was to fund or launch a series of scattered programs to try and fix things. The result was usually disappointing at best, with similar organizations competing for grant money to carry out home visits and other services. In one egregious example of what happens when services aren’t coordinated, an individual mom might have a dozen different case managers.

This time around, Dr. Gruendel conducted a six-month landscape analysis, which included extensive listening to families and the community agencies that serve them. These conversations revealed a shocking deficit of infant and toddler care, widespread intergenerational trauma, and ubiquitous implicit and explicit bias among other issues—but also a wealth of lived experience and an impressive lineup of natural community supports, including within the city’s 128 houses of worship. The word resilience came up a lot. Dr. Gruendel recalls one woman looking her in the eyes and saying, “If we weren’t already resilient, we’d be dead.”

Logan and Gruendel don’t consider themselves the leaders or the architects of the Baby Bundle. Rather, they are facilitating the redesign of resources that community members indicated would be useful for improving their own lives. The United Way team engages a group of “community messengers” who are paid for their time, engaging with families at the neighborhood level to ensure that community voice is ever present.

The Doulas

The Baby Bundle comprises a range of supports that extend well beyond the usual complement of early-childhood programs. Health care was one area that the landscape analysis illuminated. Doulas, the professionals who care for women before, during and after birth, were identified as one uniquely affordable and effective solution. Most births in Bridgeport take place at two hospitals, and ongoing health care is provided by two federally qualified health centers. Seventy percent of resident births are to moms on Medicaid—the health care program for low-income Americans, which is federally funded but administered by states. According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, only four states allow Medicaid funding for doulas. (“Maybe Connecticut could be next,” Gruendel says.)

Doulas have been around as a profession since the 1970s, but they are not well known in many of the communities where they could have the greatest impact, even though study after study shows that their presence leads to healthy outcomes for babies and mothers. Benefits include shorter labor length, less vacuum and forceps use, less use of pain medications, higher APGAR scores (an index capturing the condition of the newborn infant) and reduction in medical costs (read more here).

SciHonor Devotion, proprietor of Earth’s Natural Touch: Birth Care & Beyond, a doula collective that operates in 13 states, often has to explain what she does for a living. “Although the support we provide can lead to medical benefits, we’re not medical providers.” she says. “We provide constant guidance and support. And we are advocates for our clients.”

When young mothers lack adequate social supports, their doulas go the extra mile, helping them navigate food, transportation, baby items, car seats and more. The Earth’s Natural Touch 14-month training program covers not just childbirth but the complexities of systems, the social determinants of health, structural racism, grief and loss, and issues specific to teen pregnancy. Switching to online training during the pandemic has meant they can extend their reach globally.

According to Logan, it took a shift in attitudes within the health care profession to welcome doulas into the delivery room. Devotion concurs, describing a teen, who had just given birth and was asking to breastfeed her baby, but the medical staff ignored her, and the hospital social worker insisted that teen moms never want to breastfeed. “But this one did,” Devotion says, “and she needed someone to support her in doing so.” Another mom was suffering from postpartum preeclampsia—a condition that requires immediate treatment—and it was a doula, not the doctor or nurse, who spotted the symptoms.

The Deputy Commissioner

“Doulas can have a lot more credibility than the nurse or doctor on duty,” agrees Michael Williams, Deputy Commissioner for Operations, at Connecticut’s Department of Children and Families. He credits the Baby Bundle team for listening to the community and for adding value through data collection and science-informed technical assistance.

Williams, whose previous experience as a pastor and a social worker inform his government work, says, “For too long, authorities were confusing ‘help’ with ‘investigation’ and ‘surveillance.’ A more human public policy doesn’t blame the victim. Maltreatment prevention is still our goal, but we do that through keeping families together, not tearing them apart.” The shift in approach has brought about an increase, from 14% to 48%, of foster children placed with relatives or someone they know.

“Now that we know better,” he says, “we can do a whole lot better. And Baby Bundle fits right in the middle of that.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.