Andrea Muñeton has been a Head Start educator in California for 14 years. The work is important but greuling, she said, involving up to 80 hours a week of mental and physical labor that doesn’t end when her students head home at the end of the day.

And the pay? It doesn’t compare, she said.

“We’re underpaid, overworked and we’re not appreciated. We’re seen as, ‘Oh you’re just a day care. No, I’m not a day-care person. I’m a teacher.’”

Muñeton started off as an aide and worked her way up to full-time teacher and president of the Early Childhood Federation, an American Federation of Teachers local union in California.

Muñeton said when she was an assistant teacher, more than half of her paycheck went to health insurance, and her husband was forced to work a second job to help support their two kids, who are both Head Start students. This year, Muñeton said she reached a breaking point and considered leaving her decade-and-a-half -long career in early childhood education to apply for a job at Target.

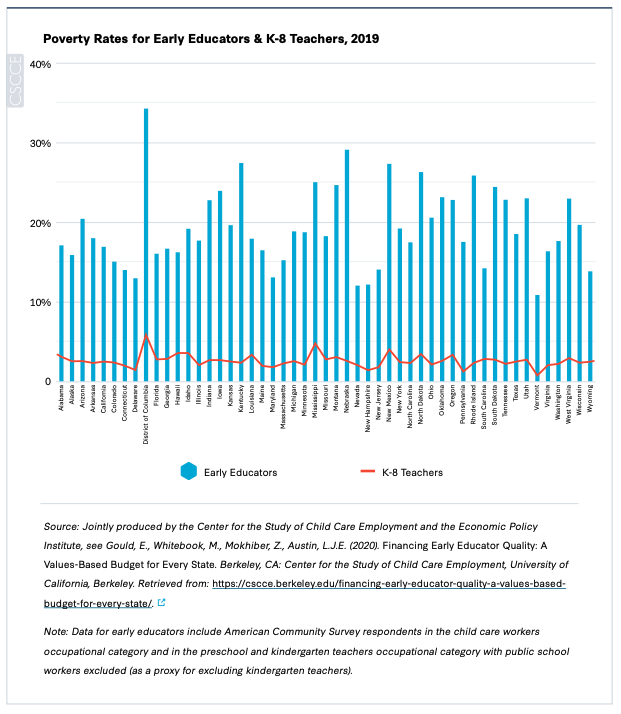

Muñeton is far from alone: child care workers nationally have one of the lowest-paid occupations, with 11% to 34% living in poverty. While the average salary of a public preschool teacher and a kindergarten teacher is about $49,000 and $60,000, respectively, the average annual salary for Head Start and other preschool teachers is about $35,000.

But this could all change over the next several years according to a new final rule recently released by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees Head Start and aims to raise annual wages for teachers in the program by about $10,000 and increase access to benefits such as high-quality, affordable health care coverage and paid leave. The rule is largely in response to the struggle to hire and retain qualified staff, which has ultimately led to classrooms closing.

Head Start organizations must comply with some elements of the ruling by October but have until August 2031 to begin providing increased pay. There is an emergency exemption for the 35% of agencies with fewer than 200 funded slots, but they must still make “measurable improvements in wages for staff over time.”

Some agencies may also be eligible for waivers for wage requirements in 2028, if the funding does not increase at a sufficient pace, which could be the rule’s greatest challenge. In order to qualify, they would need to demonstrate that implementing the pay raises would force them to cut occupied seats and show that they’re meeting certain quality requirements.

The National Head Start Association, a nonprofit organization that represents Head Start families, providers and educators, welcomed the federal announcement in an Aug. 16 press release, but expressed disappointment that the edict does not address the need for significant additional funding to fully achieve its goals and could end up forcing operators to slash staff to meet the salary mandates.

“The organization remains concerned that, if Congress and future administrations do not agree to such increases, the impact of the final rule could prove devastating, by significantly reducing the number of children and families served by Head Start programs,” the organization wrote.

While the rule is an important step forward from a policy perspective, it is a “double-edged sword” in terms of funding, according to Dan Wuori, the founder and president of Early Childhood Policy Solutions and a former kindergarten teacher and South Carolina school district administrator.

“They’re sort of stuck either way,” he said. “If they can’t attract teachers then they can’t serve kids. But if they have to compensate at a higher level to draw qualified staff then that — in the absence of new funding — could mean serving a much smaller number of children.”

Katie Hamm, deputy assistant secretary for Early Childhood Development at the Administration for Children and Families, which is overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services, said in an Aug. 30 interview that she believes the administration can partner with Congress to increase Head Start appropriations over time while simultaneously restructuring the current budget to put more money toward wages.

Khari Garvin, the director of the office of Head Start, says the hope is that the changes will position the program to recruit, attract and retain the “best and brightest talent in this field,” which “translates into better developmental outcomes for children and families.”

“The great irony … is that for too long we’ve had individuals — committed staff — working in what is an anti-poverty program, many of whom have made either poverty-level wages, or close to poverty-level wages,” he said. “And so now we’re correcting that.”

Muñeton doesn’t think Head Start teachers should have to wait so many years for this potential shift in pay, benefits and working conditions. But when — and if — it does happen, it’ll be life changing, she said.

“I’ll be able to afford maybe purchasing a house rather than renting out of my parents’. I’ll be able to tell my husband, ‘Hey, quit the other job so we can see you more often.’ I’ll be able to pay off the debt that I’m still trying to pay off monthly,” she said.

‘A really important stake in the ground’

Head Start began as an eight-week demonstration project in the 1960s, as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. Since then, the programs have reached more than 38 million children and their families, the majority of whom meet federal low-income guidelines. Currently, it serves about 650,000 children from birth to age 5 and their families, in urban, suburban and rural areas in all 50 states.

They also connect families to community and federal assistance and can help provide a career pathway for parents into early care and education: As of 2022, almost a quarter of Head Start’s 260,000 staff were parents of current or former Head Start children. The vast majority of Head Start center-based preschool teachers nationally (68%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher in early childhood education or a related field with experience. About a quarter of education staff members are Black, 30% are Latino and the vast majority are women.

The 1,600 local agencies are funded by the federal government, though many also tap into state and local revenue sources. For years, these agencies have struggled to hire and retain highly qualified educators, with turnover hitting 17% in 2023.

“We really have a crisis on our hands,” Hamm said.

For a single adult with one child, median child care worker pay does not meet a living wage in any state. Salary and benefits were cited as the top reason why almost 1 in 5 staff positions were vacant nationwide in a 2023 National Head Start Association survey. Of the 20% of Head Start and Early Head Start classrooms that were reported closed in the survey, 81% attributed the shutdowns to staffing vacancies.

These persistently low wages come from a century-long history of falsely dichotomizing care and education, according to Wuori, the policy expert and former kindergarten teacher.

“We think of early care as being almost an industrialized form of babysitting,” he said, “whereas education kicks in — from a policy level — maybe a few years later. And one of the side effects of that then is that the people who work with the youngest children are not respected as the professionals that they are. And a primary way that that is the case is through their compensation, which … lags well behind that of fast food workers and employees at big box stores.”

This new federal rule, he said, serves as a “really important stake in the ground” to rectify that mindset.

This article was published in partnership with The 74.

Amanda Geduld

Amanda is a Staff Reporter at The 74.