We have a great public library in Takoma Park, Md., but ever since the first Little Free Libraries started popping up in my neighborhood, my walks have taken a little longer. I can’t resist stopping at each one and checking out the merchandise. The serendipity of meeting an exciting and unfamiliar book on the sidewalk has weighted down my nightstand and made me feel closer to my community.

But let’s face it: My family and I already have more books than we can read in our lifetimes. Little Free Library—the organization that gave rise to the movement and that has registered more than 100,000 libraries in all 50 states (and D.C.; see below), 110 countries and seven continents—has reached the same conclusion. Maybe they’ve seen my nightstand.

“We’re known for being on White suburban lawns,” admits Greig Metzger, Little Free Library’s Executive Director. “We’ve had to re-orient our mission to meet the moment.”

The shift is entirely consonant with the Little Free Library’s origins. Todd Bol built the first one in 2009 in honor of his mother, a teacher and book lover. Over the past 12 years, the gesture has grown into a movement that prizes generosity, literacy and community. Bol died of pancreatic cancer in 2018.

There’s nothing wrong with expanding the personal libraries of suburbanites, but the organization has realized that it can unleash the power of children’s literacy by distributing free books in communities that historically have gone without adequate investment. “Children’s books are always the first to go,” says Margret Aldrich, author of The Little Free Library Book (2015) and the organization’s Director of Communications.

The books Little Free Library brings to neighborhoods without robust bookstores and libraries aren’t just high quality and age appropriate; they also tell the stories and show the pictures that resonate with children of color. So far, the Impact Library Program has provided more than 1,350 libraries at no cost to communities where books are scarce. “We get many more requests than we can fulfill,” says Aldrich.

She adds, “The research confirms the importance of getting books in their hands.” Scholars have demonstrated the impact of the “home literacy environment.” The availability of reading materials is a big part of that. It’s also vital to foster habits of reading aloud and independent reading. Children need to hear adults reading, and they need to see them reading. Aldrich confirms that librarians love Little Free Libraries. When I met Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, she proudly showed off the one in her office.

1. Little Free Library installations full of culturally relevant books, placed in high-need communities

2. Free diverse books for applying LFL stewards, purchased from independent and BIPOC-owned bookstores when possible

3. Recommended reading lists representing Black, Asian American, Indigenous, Latinx, Muslim, LGBTQ+ and other communities

4. Read in Color pledge, allowing everyone to show their support for diverse books and access downloadable resources

Last year saw the launch of the organization’s most ambitious effort yet. Although it is headquartered in Hudson, Wisc., many staff members live just over the state border in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, and in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the urge to do more for racial equity took on new urgency. Read in Color distributes books that address racism and celebrate marginalized voices—BIPOC, LGBTQ and more. The initiative involves partnering with national groups and on-the-ground organizations that really know their communities.

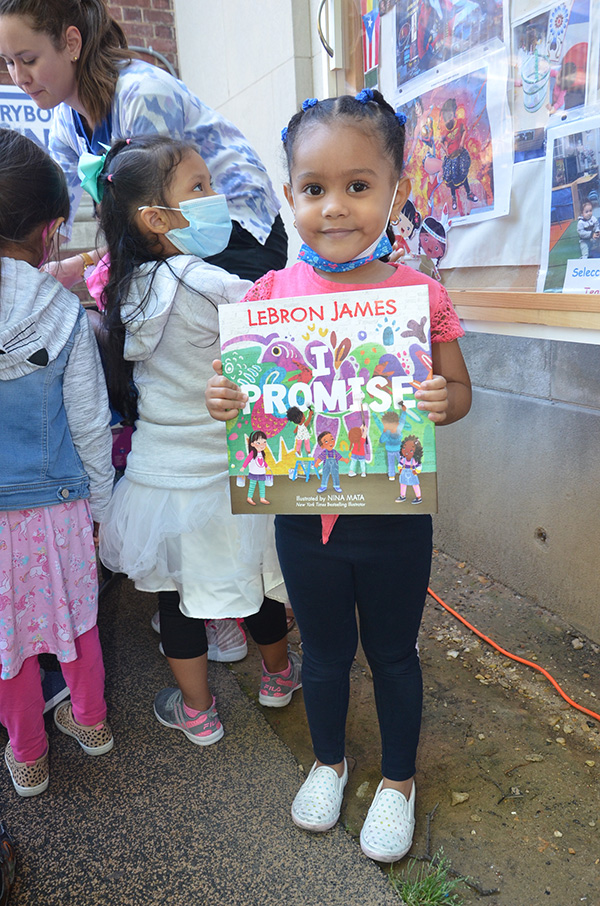

In May, to observe the centenary of a race massacre, Read in Color kicked off in Tulsa, Okla., in conjunction with Reading Partners and HarperCollins, building and stocking 26 new book-sharing boxes. “Every single person here,” said Dr. Tiffany Crutcher—an activist whose twin brother was killed by police in 2016—“believes that our children deserve schools that are palaces, homes that are healthy, neighborhoods that are safe, and on the simplest level, they deserve to open a book and see themselves reflected in its pages.” Read in Color is also rolling out in New York, Chicago and Boston.

Last month, I attended the Read in Color ribbon-cutting ceremony at CentroNía, one of D.C.’s largest multicultural child care providers. Watching a dozen or so young children assault the little ribbon on the little house with their little scissors gave me one of the most unmistakable jolts of optimism in recent memory.

Jordi Hutchinson, executive director of event cosponsor Everybody Wins DC, said, “By increasing access to engaging reading materials that celebrate diversity, inclusion and social justice, we are giving children new ways to develop critical social emotional skills such as self-respect and empathy while also promoting understanding across communities and cultures.”

The construction firm Van Metre unveiled an example of the lovingly detailed miniature house-shaped libraries they were donating, and CentroNía’s Michael Yacob read Little Libraries, Big Heroes to a group of preschoolers, demonstrating the power of story time—and of Bol’s vision.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.