As kids head back to school—in person, hybrid or remote—a wistfulness for the missed opportunities of summer might be setting in. That trip to the beach didn’t materialize, the crowded local hiking trails were nerve-wracking and even visits to Gram’s house had to be curtailed. But that doesn’t mean the time for adventure has passed.

Winter is coming…and so is adventure.

The Seatuck Environmental Association in Islip, New York, is a conservation organization with popular outdoor education offerings that Long Island families rely on for connection and inspiration. The pandemic’s sudden arrival forced a quick reassessment of how to stay connected to the children and families.

Starting with the premise that many families might not have easy access to even ordinary items like binoculars or magnifying glasses, the team created a series of daily nature challenges. Their venture—and the enthusiastic responses it provoked—can create a template for any of us seeking to keep adventure alive even as winter approaches.

Starting with the premise that many families might not have easy access to even ordinary items like binoculars or magnifying glasses, the team created a series of daily nature challenges. Their venture—and the enthusiastic responses it provoked—can create a template for any of us seeking to keep adventure alive even as winter approaches.

For those wishing to create mini field trips to nurture their children’s connection with nature, Seatuck’s Education Director Peter Walsh advises to start small and close at hand.

“It’s really just about exploring and it can be something as simple as, ‘Go watch the sunset. Tonight, try to see it from your yard or window or somewhere safe, and take a picture of it or draw it. Don’t do anything else: just enjoy a sunset.’”

The operating principle in these mini adventures is wonder, he says, and wonder doesn’t require anything except presence. Just be there and notice what’s there to be noticed. Some examples:

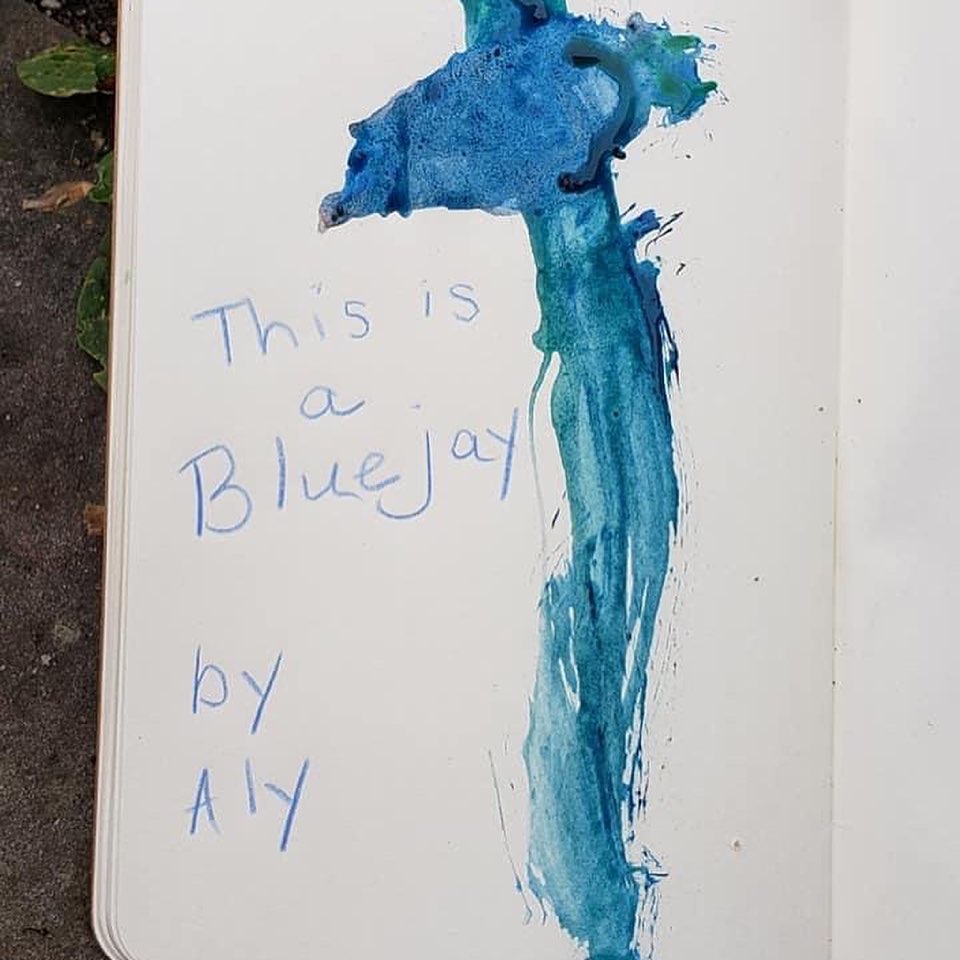

- Observe different kinds of birds, then draw a picture of them (adults, too: pick up those colored pencils and give it a go!) or have a conversation while describing the birds in as much detail as each of you can remember: the size of the bird, its colors, the shape of the feathers, beaks and feet.

- If you have any leftover color swatches from the paint store, let the children take them along on their walk and see if they can find those colors in nature.

- Find an anthill and, from a respectful distance, sit back and watch them work. If that doesn’t provoke at least a little wonder, well, pay closer attention.

- Listen to the sound of your sneakers walking over crisp fallen leaves.

- How would you describe the smell of freshly mown grass?

Don’t make the adventure a test (“Let’s see how much you remember, Jenny”), an opportunity for a lecture or a chore. The second it becomes a “have to,” is the moment it quits being an adventure. Children don’t need to be instructed every moment they’re outdoors to “get them to learn.” When they’re outdoors and they’re looking, they’re learning. Maybe synthesize some of that when you get back to the house, but don’t let your drive to pack education into every moment keep them (and you) from actually being in the moment.

Don’t make the adventure a test (“Let’s see how much you remember, Jenny”), an opportunity for a lecture or a chore. The second it becomes a “have to,” is the moment it quits being an adventure. Children don’t need to be instructed every moment they’re outdoors to “get them to learn.” When they’re outdoors and they’re looking, they’re learning. Maybe synthesize some of that when you get back to the house, but don’t let your drive to pack education into every moment keep them (and you) from actually being in the moment.

Remember that adventures can be had in all kinds of weather. There’s an old joke from the Midwest, where people play hockey, curling, go ice fishing, cross-country skiing and ice caving in the worst weather: “There’s no bad weather, only bad clothes.” So dress your kiddos well and take them out year-round. Kids love holding their wee faces up to the rain, letting snowflakes hit the tongue, splashing in puddles, building snow forts, and sledding or tubing down snowy hills. Do you remember that you used to love that, too?

The Seatuck team’s challenges frequently center around becoming aware of the beauty that surrounds all of us, every day.

“One of the experiments is, ‘It’s going to be clear tonight, so watch the sky at sunset and notice how many different colors you can see in 10 minutes,’” he says. “When we did it, we found five different shades of blue.”

If you’re really observing and not just passing by, nature presents an abundance of beautiful objets d’art. Make a frame from an old box or paper; create an artwork by placing the frame around that incredible rock or shiny bug your preschooler found, then take a picture. Maybe no one had noticed before how gorgeous those beetle’s wings are, but once a child really sees them, they will never forget that iridescence.

Quests fuel many adventures, and the quest can be for something as mundane as “Find five different shades of green,” or “Find three different kinds of bugs,” or “Can we find two different kinds of pinecones today?” “Find five kinds of leaves. Look how different they are from each other.”

If you find an abundance of green leaves, let the kids gather some up and smush them with a mortar and pestle (or DIY equivalent, such as a big rock and a little rock), then add water and let the children paint with the chlorophyll. The paint will have the color and consistency of watercolor, so don’t expect vibrant pigment. But it will be cool.

Add a community element by creating a scavenger hunt that the children design themselves. Leave the things where you and the kids spotted them, then give the list to your neighbors or other family members and see how many they can find. (Then celebrate the win no matter how small. As any Greek hero would tell us, a victory isn’t a victory without some festivity.)

Save your toilet paper rolls and paper towel rolls because those things are adventurer treasure. One alone becomes a telescope, two taped together make binoculars (“The kids will swear it makes everything closer,” Walsh says. “That’s OK. It’s all about getting them to focus on an object and really look at that one specific thing.”). A single paper towel roll becomes a “toot-da-doo!” because who can resist holding one up and toodling triumphantly? Several being “played” at once becomes a cacophony and sometimes, a little cacophony is good for the soul.

Save your toilet paper rolls and paper towel rolls because those things are adventurer treasure. One alone becomes a telescope, two taped together make binoculars (“The kids will swear it makes everything closer,” Walsh says. “That’s OK. It’s all about getting them to focus on an object and really look at that one specific thing.”). A single paper towel roll becomes a “toot-da-doo!” because who can resist holding one up and toodling triumphantly? Several being “played” at once becomes a cacophony and sometimes, a little cacophony is good for the soul.

When you head out, remember to take a paper bag or backpack to schlep items for the collection—because nine times out of ten, there will be a collection. Practically every kid everywhere will want to collect something—rocks, bug carcasses, sticks, shells, feathers, bark, acorns, pinecones, leaves—and you want to make sure the artifacts end up in the bag and not in your pockets (though, tell the truth: Can you go on a hike or visit the beach without coming back with rocks in your pockets?).

For those with very little children, Walsh and his team recommend the 30-foot hike.

“With the 18-months to 3-year-old group, just let the kids lead the walk,” he says. “They’re in charge of the hike. You make sure they’re safe, but you follow their lead and help them explore the things they’re touching and looking at. You don’t have to go anywhere big or far. Just let them lead.”

British adventurer and author Alastair Humphreys coined the term “microadventure” to describe these small-scale outings. In his book, Microadventures: Local Discoveries for Great Escapes,” he laid out the elements of a great adventure for children.

“If it involves food, getting wet or muddy, fire or breaking the rules, the kids will love it. … Involve kids in the planning and talk to them when you’re doing it. Point out things that even you take for granted and point out to the children what’s safe and what isn’t. They take in way more than you think. What’s the worst that could happen? Plan accordingly and pack a change of clothes.”

To which Walsh adds, “And a towel!”

Walsh stresses that there is no right or wrong way to create a mini adventure—the point is just to get outside and to feel connected to other people in the world by sharing their experiences and discoveries. The important thing is to interact with the environment, not to just passively sit in it. Especially don’t sit in the environment and scroll on your device. This is mutual discovery, not nature as babysitter.

“We see so much of that,” he says. “It’s this real passive thing of not investigating, not playing with their environment, just walking past it. I think a lot of it is that the younger parents grew up as part of this generation that just didn’t go out and explore outdoor spaces with free, unstructured time. So, when they go somewhere, they don’t really know how to interact with the physical world.

“It’s true with some of the younger teachers as well—the idea of exploring is really foreign to them. We say, ‘Try to find five different kinds of rocks,’ and teachers come back and say, ‘Do you really think we’ll be able to find five different kinds of rocks?’ and then they’re amazed that they found 10.

“We want to keep the idea of these nature challenges really open-ended. If we give them a worksheet or tell them, ‘Try to identify these five kinds of clouds,’ they will spend all their time trying to answer the question correctly and then feel that they weren’t successful if they didn’t find exactly those things.

“So, keep it about wonder and fun,” he says. “If the kids really love it, they’ll want more.”

As long as you stay focused on those two things—wonder and fun—neither you nor the kids will feel inadequate or unprepared. Just by being there, you have everything you need.

Though you might want to bring your toot-da-doo.

All photographs courtesy of Seatuck Environmental Association.

More reading:

- PopUp Storywalk Combines Great Stories with the Great Outdoors

- The Benefits of Wet Hands and Muddy Feet: Interview with Richard Louv

- Mind Field: One Topic, Six Experts: PLAY

- Playful Learning in Pittsburgh: the Park as Classroom

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.